Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

On July 1, Canadians from coast to coast to coast will mark the 150th anniversary of Confederation. Milestones like this often lead to lists, which attempt to enumerate achievements and note the figures who made history. One of the things that has struck me in seeing these lists is how frequently Canadian medical achievements are cited. Yes, as you might predict, Banting and Best’s discovery of insulin ranks high on many lists. But you’ll also find the invention of Pablum, open heart surgery, the discovery of the cystic fibrosis gene, stem cells, T-cell receptors — to name but a few. Canadians take pride in these breakthroughs, as they rightfully should.

Perhaps it’s because of the lens I view the world through, but I can’t help notice that in addition to being Canadian, these achievements were the result of work by clinician-scientists or created thanks to close collaborations between basic scientists and clinician scientists in our Canadian academic health science centres. I don’t think that is a coincidence. Being a bridge between the needs of patients you treat and the research you conduct provides a unique vantage point that can help identify solutions. And, I would argue that because Canada has historically supported and cultivated clinician-scientists, this nation has “punched above its weight” when it comes to delivering medical breakthroughs to the world.

I might sound un-Canadian to boast, but a growing body of literature is helping to make that case. For many years, discussions of clinician-scientist training initiatives inevitably meant talking about MD/PhD programs, acknowledging that many clinician scientists are also educated via postgraduate programs including the Clinician Investigator Program. And research on the success of MD/PhD programs was largely based on American studies. However, our conversations are becoming more nuanced and specific to what is happening in Canada. Research, led in large part by MD/PhD students themselves, is providing a broader understanding of how our programs are performing. A paper published in CMAJ Open in April 2017 found that 83 per cent of MD/PhD graduates surveyed had academic appointments. Three-quarters of respondents had published three or more first-author papers during their studies. Yet, the paper also reveals some challenges. For example, only 36 per cent of graduates reported spending 50 per cent or more of their time on research. For comparison, the average from a comparable American study was 64 per cent. The authors suggest:

“The fact that Canadian MD/PhD graduates typically pursue careers in academia yet dedicate less time to research than American MD/PhDs suggests that academic health sciences centres in Canada many not be structured to support physician-scientists in positions with the majority of time dedicated to research, particularly given the decline of federal funding programs to support the salary of both clinician-scientist and PhD-only investigators.”

In other words, we’re succeeding not because of our support structures, but, in some cases, despite the lack of them.

But importantly, the conversation is evolving to recognize that MD/PhD programs are not the only pathway to development of clinician-scientists. In addition to the Clinician Investigator Program, a RCPSC post-MD Program in which 140 of our residents are training, U of T Medicine is offering new programs that aim to spark an interest in research among all of our physicians, and equip them with the skills to pursue those interests. This includes the introduction of the Integrated Physician Scientist Training Pathway with a strong focus on competency-based education and integration of clinical medicine and research.

Better understanding the opportunities and limitations of our MD/PhD programs will help us improve them and identify barriers that we can overcome. Introducing new programs and diversifying the options will also help ensure we are adaptive and responsive to the needs of our different learners. I think this provides a foundation that will allow physician-scientists to define the direction of medicine in Canada for the next 150 years.

But what do you think? To mark Canada’s sesquicentennial, U of T Medicine wants you to answer this question: How will you create a healthier future? You can write down your response and post it on the new wall display near the MSB cafeteria. We’re looking for your ideas on how we can build upon the made-in-Canada gains we’ve made, recognizing that there remains much further we can go.

Happy Canada Day!

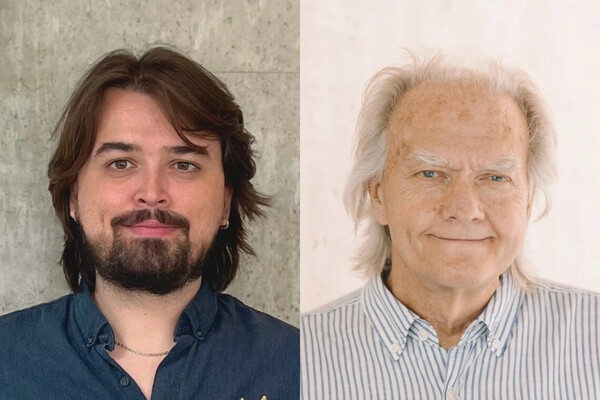

Norman Rosenblum

Associate Dean, Physician Scientist Training

Faculty of Medicine