Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

Jim Oldfield

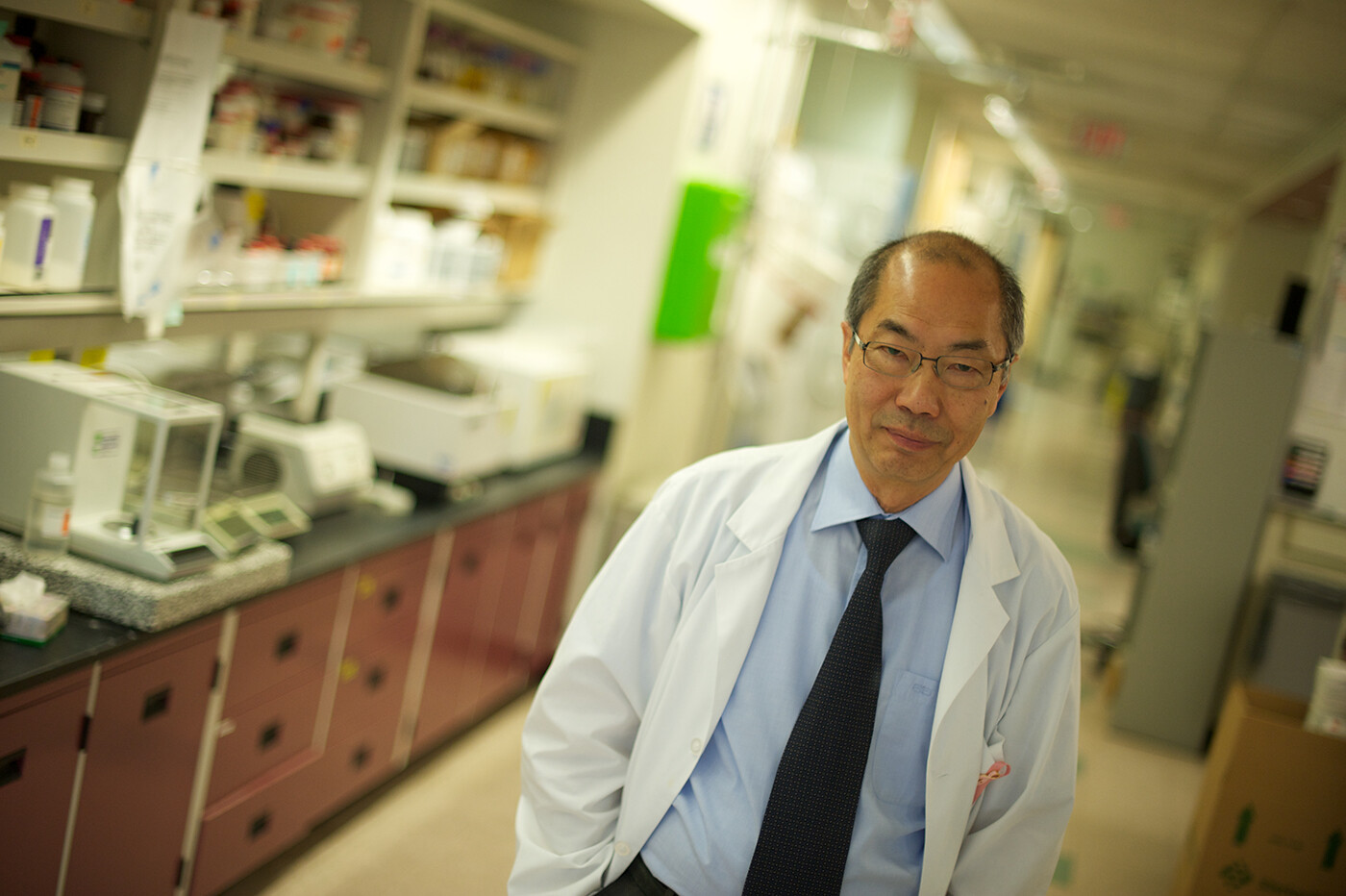

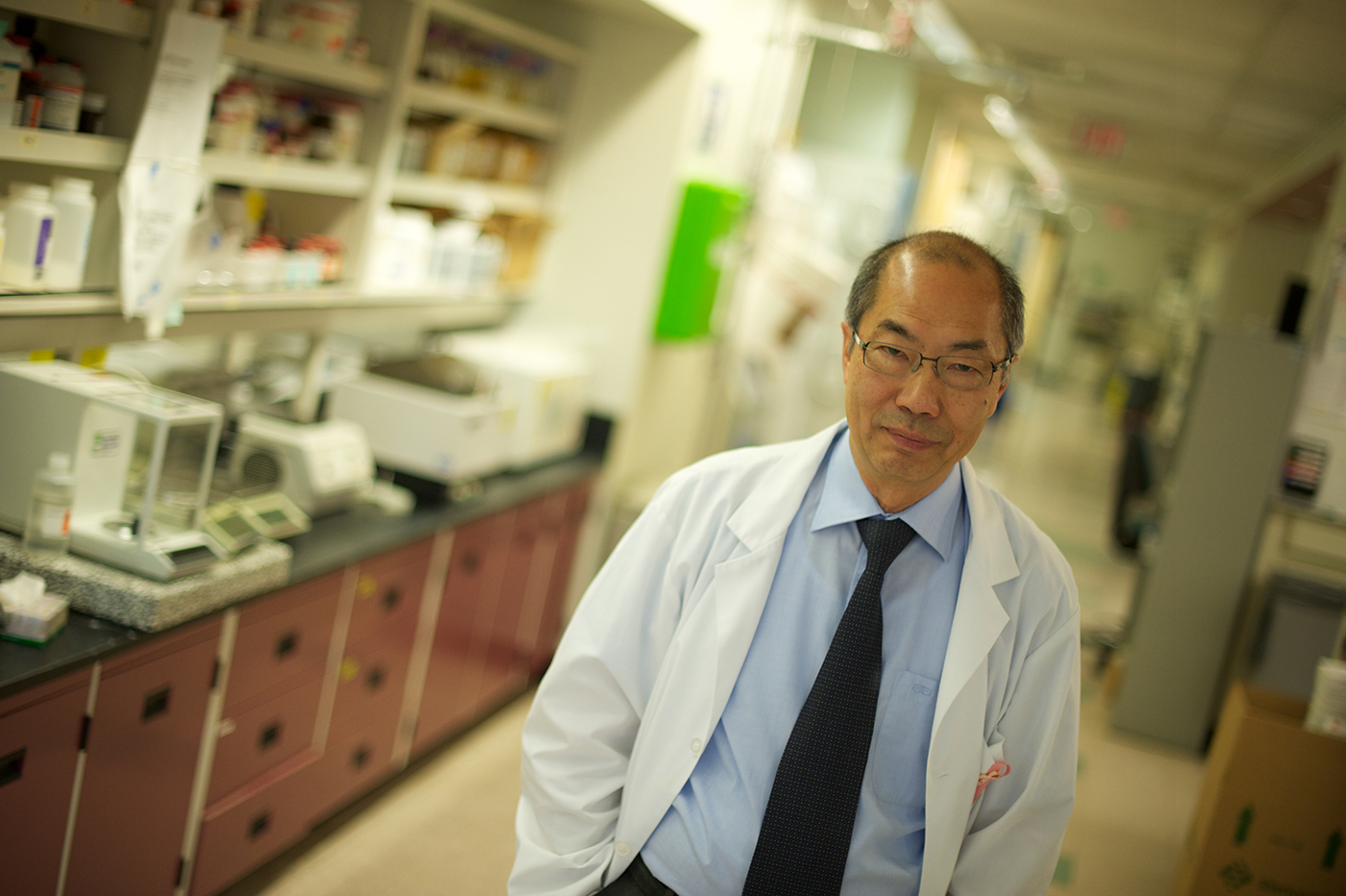

Professor Tak Mak still recalls the surprise he felt on learning that Canada’s Medical Research Council granted him more money than he requested. It was the early 1980s, and Mak was an assistant professor competing for funds with the other scientists pushing Canada into a global revolution in cell biology.

“I applied for $50,000 and they gave me 67,” says Mak, who is today a professor of medical biophysics and immunology at the University of Toronto and a senior scientist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, renowned for a career that has spanned biochemistry, virology, genetics, cancer metabolism and clinical therapy. “Over the years, Canada’s granting agencies have really supported my work in a very paramount way.”

That relationship came full circle in a sense today, as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research named Mak the recipient of its prestigious Gold Leaf Prize for Discovery, which recognizes ground-breaking research and comes with a medal and $100,000.

The award will support new research, but for Mak it’s also a recognition that CIHR’s investments in his work was money well spent. “We did all we could to achieve the scientific excellence and innovation CIHR wanted, and to some extent we have fulfilled that intention,” says Mak. “That is gratifying, because when a person or agency is really generous, you don’t want to disappoint them.”

Far from being a disappointment, Mak has given Canadians many reasons to be proud.

Mak’s lab co-discovered the T cell receptor in 1984 — a finding that fundamentally changed how scientists understood the immune system and led to major advances in T cell biology, autoimmune disease and immunotherapy. His lab was also one of the first to generate knockout mice, which enabled scientists worldwide to study the effects of individual genes. And Mak co-founded Agios Pharmaceuticals, whose leukemia drug IDHIFA became the first clinically approved therapy to target cancer metabolism in 2017.

Earlier this year, Mak’s group used genetics to show that the nervous system and immune system communicate through a molecule called acetylcholine. The discovery confirmed a long-suspected but poorly understood link between the two systems, and again opened several new avenues of research.

Mak attributes these and other achievements in part to the cooperation of the Canadian scientific community. “One thing that makes Canada great is congenial and collaborative scientists across the land,” he says. “And looking back at the metamorphosis of our lab from field to field to field, it was in many cases through work with Canadian scientists.”

To take two examples: the development of genetically altered mice, Mak says, would not have happened without close collaboration from stem cell biologist and University Professor Janet Rossant. And when his lab shifted focus from immunology to cancer, Mak says the approach and vision of the late molecular genetics professor Anthony Pawson was invaluable.

Mak has also benefitted from many talented trainees who have passed through his lab. That group now numbers over 130, and includes a university president, medical school deans, and dozens of institute directors and departmental chairs. Mak often sees visits these former colleagues — most recently on a trip to the Technical University of Munich this week, where he received an honorary professorship — and he says that seeing this extended ‘family’ succeed brings great gratification. “There’s no substitute for that. I am reminded of the Indian proverb, ‘All the flowers of all the tomorrows are in the seeds of today.’”

Mak offers special praise for the mentorship he received as a young researcher, including his time in the lab of Nobel laureate Howard Temin, and his early years in Toronto working with Ernest McCulloch and James Till, who discovered stem cells. “McCulloch taught me to think differently, to have original ideas and integrate my thoughts. Till was a staunch, vigorous physicist, who insisted that all results be statistically significant and re-confirmed. The two together made an almost perfect mentorship for me.”

Today, that oblique but rigorous approach to science still informs Mak’s thinking, which increasingly centres on inflammation, another frontier in medical science. Inflammation is essential to the immune system’s ability to fight germs, but it can create problems that result in autoimmune diseases. Researchers are recognizing the role of inflammation in neurodegeneration, cardiac disease and many other conditions, and in our ability to fight cancer.

“We need to understand that important ying and yang,” says Mak. “When the thermostat of inflammation needs to be up, and when certain aspects need to come down — this is where we need to focus.”

Mak is still very engaged with these and other scientific questions. The ‘party,’ he notes, is still going strong. “I have tremendous gratitude for the support I’ve received from the Canadian scientific community and from CIHR,” he says. “When you’re a kid you get to play with toys and figure things out, and you’re not supposed to do that as an adult. But science is like toys for adults, and we get to discover everything there is.”