Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- News & Events

- Recent News

- My Experience on COVID’s ‘Other’ Front Line

My Experience on COVID’s ‘Other’ Front Line

On March 11, 2020, I stood in the University of Toronto’s Combined Containment Level 3 (C-CL3) labs, staring hopefully at a microscope’s screen. I held my breath. Did we have it?

It was a week that, for many people, marked the start of COVID-19’s impact on their daily lives. But not for my colleagues and me in the C-CL3 labs. As Toronto’s only biosafe and biosecure facility where academic scientists can safely work with highly-infectious and impactful pathogens, we’d been gearing up for more than two months for the virus that would be named SARS-CoV-2.

I first began reading about unusual clusters of pneumonia in China in the weeks leading up to the 2019 holiday break. In infectious disease research circles, there’s always a sense of waiting for the next pandemic pathogen to emerge. We know it’s a matter of when, not if.

I remember discussing whether this new virus could be ‘it’ with Dr. Scott Gray-Owen, the C-CL3 labs’ director. Neither of us could tell for sure at that point, but if it was what we thought it could be, we would need to get ready quickly.

I’ve been working in U of T’s C-CL3 labs since the facility launched in the early 2000s. As a doctoral student pursuing HIV research, I was even paid to help set up the space — unpacking incubators and things like that. Then in 2008, just as I was finishing up my PhD, I learned the facility’s manager was moving on and I was asked to consider taking on her role.

It seemed like a lucky coincidence. I was burnt out and questioning whether I wanted a life as an academic. I thought I'd help run the lab for a couple of years, start my family and then figure out what I wanted to do next. Thirteen years (and three children) later, my work still revolves around the facility!

For most of that time, the labs were a pretty low-key place. We had a maximum complement of eight primary investigators and their teams working out of the space. A busy day would be when four people would want to come in on the same day. There was always interesting work happening, but I had lots of time to discuss experimental plans with the graduate students working in the facility or train up the next new post-doc joining one of the labs.

However, by the end of January 2020, we could see our relatively calm, low-key days would soon be over. It was clear this novel coronavirus wasn’t going to be contained.

As the Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Research Operations Officer, I didn’t sleep much in February. Questions kept circulating in my head. How do we prepare? What resources do we need? How do we absorb what's going to happen?

Toronto’s research community was eager to contribute and ready to mobilize against SARS-CoV-2. We knew our lab was going to play an essential role in their work, but we had a few major challenges to overcome first.

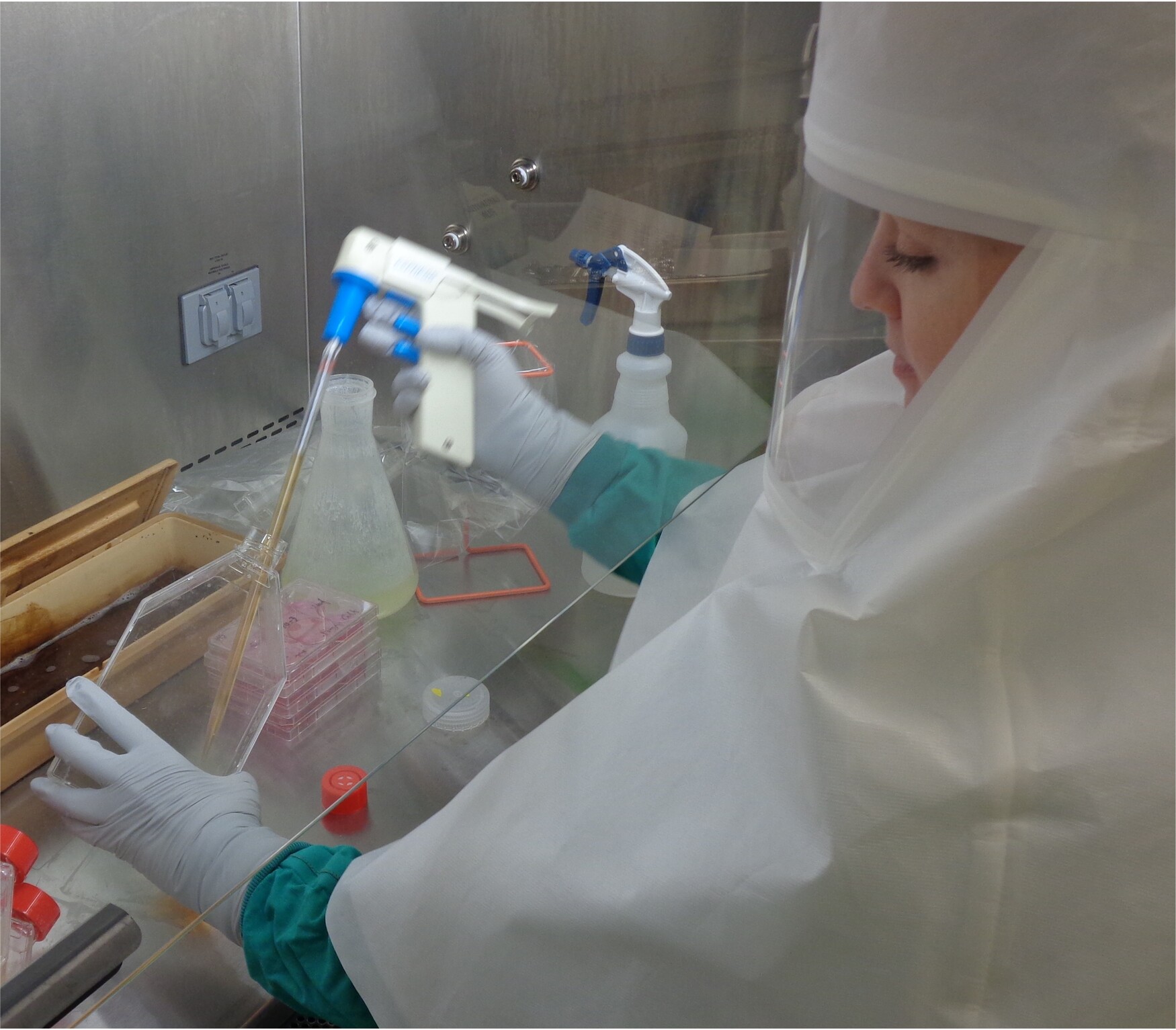

Most people don’t realize it takes months to train someone to work in a CL3 lab – time we didn’t have. And, with ours being the only facility of its kind in the entire city, there also aren’t many people out there with the training to begin with. To address this, two fully-trained grad students, Patrick Budylowski and Furkan Guvenc, pivoted into new roles as my full-time partners in the C-CL3 labs.

Fortunately, we didn’t have to worry about the cost of what we were doing. Very early on in 2020, Faculty and University leadership assured us they recognized the C-CL3 was going to be a critical resource in the city’s response to COVID and that they’d be there to provide any financial support that we needed. Those assurances were a huge relief.

The medical and research community also started to rally around us. The reality of research is that it can be a competitive space, but SARS-CoV-2 brought everyone together. Everyone was asking how they could utilize the C-CL3 labs: cell biologists with high throughput screening for drug discovery, cardiologists with tissue modeling systems to look at pathogenesis, respirologists looking at infection in their primary cell systems. It was really moving to see everyone working towards a singular goal.

I began by adapting a new regulatory program for SARS-CoV-2. It’s not the glamorous part of science, but obtaining the approvals for work with high-risk pathogens takes a lot of effort and detailed communications with federal regulators. We had to fully rewrite our program to mitigate all the risks that would come with a new aerosolized pathogen which, at the time, we didn’t know much about. That took my colleagues at the Biosafety Office and me working flat out for more than four weeks to complete.

Then, it was also a matter of gearing up. We didn't have enough of the exact types of personal protective equipment we needed for the new work but, of course, by then there was a global rush on this kind of equipment. That added a lot to our stress levels.

I’ll never forget what it felt like when I could see on the microscope screen that we had SARS-CoV-2 in our lab. This is what we'd all been waiting for — we were going to be able to work with a novel virus that only a couple other labs in the world had ever cultured.

Our biggest challenge, however, was that we didn’t yet have any virus with which we could work. We started investigating importing the isolated pathogen from outside Canada in February, but hit major snags as the regulatory landscape figured out how to manage a highly-infectious novel pathogen of global impact.

By then, though, we had our first domestic case. Circumstances aligned, in a way. Professor Samira Mubareka of the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology was a long-time researcher in the C-CL3 labs. She had dedicated her career at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre to understanding aerosol transmission of pathogens and looking for emerging viruses in animal samples. And Sunnybrook is where Canada’s first case just happened to present. The virus was here and, using the C-CL3 labs, Dr. Mubareka and her colleagues were able to isolate it for research purposes in early March.

I’ll never forget what it felt like when I could see on the microscope screen that we had SARS-CoV-2 in our lab. This is what we'd all been waiting for — we were going to be able to work with a novel virus that only a couple other labs in the world had ever cultured. The scientist side of me was thrilled and intrigued, but I also knew the next couple years wouldn’t be easy for everyone outside the lab. We could tell, even then, that this wasn’t going to be 2003 and SARS-CoV-1. This wasn’t going away.

Now armed with the isolated virus, we went full steam ahead. First, we proceeded to share our isolate — helping all other Canadian CL3 labs get set up with their own research programs. Then we turned to assessing and responding to the many requests we were getting from researchers and industry wanting us to run experiments for them.

That was something new for us. We hadn't provided service at any point in the C-CL3 labs’ past. To help get projects started quickly, academic partners looked to us to run their SARS-CoV-2 experiments on their behalf. Furkan, Pat and I became the crew on the ground, and I dedicated myself to initiating training for groups who were going to run long-term CL3 studies. We were helping scientists and public agencies investigate things like if the virus could survive on respirators or be transmitted by handling currency. And of course there were drug screening and vaccine projects. Everyone wanted to test everything, and the only place they could run their experiments in Toronto was in our facility. With the backing of the University and the Faculty – and catalyzed by the remarkable gift from the Temerty family – we moved to operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, focusing exclusively on SARS-CoV-2 projects. Even then it was hard to keep up.

We made a conscious decision to prioritize academic research, but were also getting inundated with calls from industry looking for help with their COVID projects. That was also new for us. People would call us out of the blue, from all over the world, and say “we've got this thing and it’s going to solve the pandemic.” We’d run through a list of questions: “Have you done any other testing on it? Have you experimented with level 2 pathogens? Do you have any proof of concept?” We were already so stretched for personnel and space, we had to be ruthless with what we could take on.

One project we did pursue in partnership with industry was with Quebec-based company, I3 Biosciences, which manufactures face masks with a specialized antimicrobial coating. We were able to run tests that validated the coating was effective in deactivating SARS-CoV-2. Later on, we also worked with Edesa, another Canadian biotechnology company, on its novel immunotherapeutic. I wished there were more hours and we could have done even more.

It’s a wish I wasn’t alone in making — and one that has helped lead to a new push to expand infectious disease research capacity in Toronto. The university, together with several major hospital partners, has made better preparation for emerging pathogen outbreaks a key strategic priority. We want to build upon the networks and partnerships that we saw worked so well during COVID, while also ensuring we have the space, equipment and trained scientists to proactively prepare for whatever pathogens come next.

I’m honoured that, after thirteen years of working as the C-CL3 Facility Manager and then as Temerty Medicine’s Research Operations Officer, I’ll be able to contribute to this new vision in an expanded role focused on the initiative’s strategy and operations.

Now that COVID has become our new normal, I’ve had a few moments to reflect on all we accomplished in the past 22 months. I can’t help but feel proud — not only for what we did here at U of T, but also to be a part of a global basic science community that has more than demonstrated our value.

I like to remind friends and family members that researchers weren’t starting from scratch in our response to COVID — vaccines and therapies didn’t spring out of thin air. They are the result of decades of incremental steps that science takes as it winds its way to solutions. Suddenly, all of that work coalesced. Research few people in the public knew about or understood was able be translated into real, useful applications. Basic science is literally saving the world.

I’m grateful to have played my small part in helping to make that possible — and excited by the larger role the C-CL3 labs and I will be able to play in helping to respond to and protect us from infectious diseases in the future.

Dr. Natasha Christie-Holmes (PhD’08) is the Director, Strategy and Operations for U of T’s Emerging and Pandemic Infections Consortium (EPIC).

News