Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- News & Events

- Recent News

- Laszlo Radvanyi on Botany, Clinical Biochemistry and Cancer Biotherapeutics

Laszlo Radvanyi on Botany, Clinical Biochemistry and Cancer Biotherapeutics

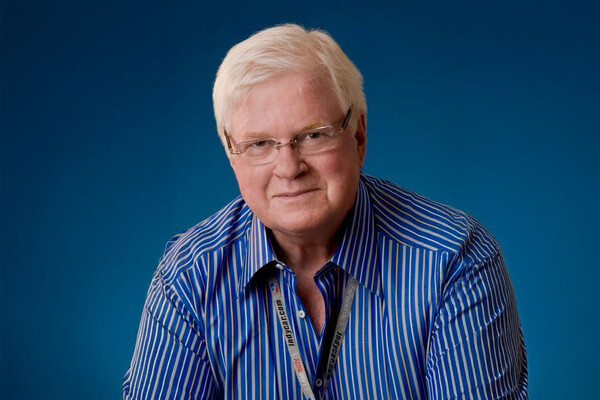

Dr. Laszlo Radvanyi (BSc ’86, MSc ’90, PhD ’96) is a professor and scientist in the biotechnology field. Following post-doctoral work in the Joslin Diabetes Center at Harvard University, he worked for Sanofi Pasteur Canada as a Senior Scientist and then as a Professor in the Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology at the University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center. He then went on to being the founding Chief Scientific Officer at Lion Biotechnologies (recently renamed Iovance Therapeutics) in Tampa, Florida before becoming a Senior Vice President and Global Head of the Immuno-Oncology Translational Innovation Platform and Senior Scientific Advisor at EMD Serono (Merck KGaA) located in the Boston, MA area. He is currently the President and Scientific Director of the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) located at the MaRS Discovery District in Toronto.

I always tell my graduate students, “If you are working on a research project or research problem that doesn’t keep you up at night, then you shouldn’t be working on it.”

In May 2018, Dr. Laszlo Radvanyi was appointed President and Scientific Director of the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR). A scientist, professor and leader in the international biotech and pharma industry, he has worked in cancer immunology and immunotherapy for over 25 years. We asked him about what drew him to cancer research and immunology, the benefits of a good mentor, and his advice for students looking to discover their true path.

You have been President and Scientific Director of the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research for over a year now. What does that role involve?

I feel like I am a big connector of dots, or a master builder collecting building blocks and working with a construction team to make new and exciting things. In the case of OICR, these ideas lead to new collaborative translational research programs in cancer across Ontario –ultimately leading to new therapies that improve the lives of cancer patients. This impact is very inspiring to me on a daily basis.

In essence, I play the role of a CEO for the organization, reporting and answerable to a world-class board of directors and scientific advisory board. I also wear the “science hat” working daily with scientific leads and external investigator groups in driving our programs and translational research vision forward, as well as working toward our next strategic goals. OICR is run much like a corporation with checks and balances and continual assessment and tweaking of its research programs, finances, and risks to maximize impact.

There is a lot of creativity and “out of the box” thinking that goes into it. I can use all my scientific expertise and my experience in academia and biotech and pharma. And I spend a lot of time meeting people, listening and learning from them and bringing disparate ideas and multi-disciplinary perspectives together. For a scientist with my experience and background it has really been a dream job.

You’ve also worked in a variety of positions in the academic world and in industry. What do you like about each?

I think both worlds offer unique and powerful learning and development opportunities. My first passion has always been academia and the love of exploration. I also enjoy “chaos” in a certain way and the challenges this brings in needing to tie things together to come to a solution. This is also a major characteristic of biological systems that are by nature chaotic and difficult to predict. This is probably what drove me to fall in love with immunology and then cancer immunology – studying perhaps the most “chaotic” of biological systems where multiple cells, pathways, and locations are constantly changing over time, influenced by the environment. The things you do to tinker with this system can also have both short-term and long-term effects, which can be difficult to predict.

After finishing my postdoctoral work and doing a short stint as a scientist at Sanofi Pasteur here in Toronto, I went to the University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center, where I was a Professor for 10 years developing new cell-based immunotherapies for cancer. One of my joys was mentoring graduate students and post-docs, being able to help them publish, build a foundation for their careers and helping them navigate complex career opportunities.

After 10 years in academia at MD Anderson, I took a hard look at my career and thought about how to channel some of my energy into the business world to translate my work into new therapies for patients – to have that more direct clinical impact we dream about as scientists. I had a chance to help start a biotech company as the founding Chief Scientific Officer, which is now called Iovance Biotherapeutics, commercializing a unique cell therapy for cancer using tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) that I was working on at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

After setting up the Iovance’s research infrastructure and helping lead them into their first clinical trials, I moved beyond that to work in a large pharma company called EMD Serono (Merck KGaA) as their global head of immuno-oncology research and development. It was a great opportunity to get an “inside scoop” of what drug development is really all about in pharma. Coming back to Ontario, I am now in a position to use all these experiences and learnings in my new role at OICR.

When did you discover your passion for biology and then immunology?

I’ve had a passion for biology since high school. In university, I was inspired by great botany teachers, including Dr. Johan Hellebust in plant biochemistry and Verna Higgins in plant pathology. This drew me to cell biology and biochemistry, and a Master’s degree in Botany at U of T in Professor Frank DiCosmo’s lab studying calcium-binding proteins and cell signalling in plant cells.

I was intrigued by the fact that plants could be the basis for new therapeutics and drugs. And this link to medicine during my Master’s degree drew me into the medical sciences and biochemistry and immunology – as well as a 90-degree turn in my career away from botany and into biomedical research for my PhD, where I joined the clinical biochemistry graduate program.

Then, during the first year of my PhD I took a graduate course in the Department of Medical Biophysics in the Ontario Cancer Institute, where a series of lectures on the immunological mechanisms in cancer by Professor Richard Miller, the founding Chair of the Immunology Department, changed my life. I fell in love with immunology and have been at it ever since.

You’ve had a lot of mentors along your career path. Tell us about some of them and how they helped you.

My Master’s degree supervisor Professor Frank DiCosmo unleashed in me a real curiosity and drive to be a scientist, by just letting me explore. He also invited me to present my work with him, which was a strong message to me that he didn’t just take credit because he was the lab supervisor. That’s how I run my lab too now, giving young scientists the credit for their work and building up their careers.

Another mentor was Professor Joan Boggs, who was the graduate coordinator of the Clinical Biochemistry Department where I did my PhD. When I was unsure and somewhat confused as to what to where to find my niche, she took me under her wing, gave me good advice and encouraged me to hang in there. She also helped connect me with Professor Gordon Mills, who became my co-PhD supervisor and a long-time mentor and role model.

What advice do you have for current U of T students?

The first piece of advice is: Don’t be afraid of change and alter your direction. If you feel you are not happy with what you are doing career wise, and an opportunity comes where you can change, then take it seriously. If it makes sense to you deep down, then take the leap. Sometimes you also need to step back and re-evaluate: where am I going, what am I doing, is this really for me? Use your crystal ball and think about five to ten years down the line, where you see yourself — try to do that exercise once in a while. Don’t just forge, forge, forge without thinking. But, don’t over rationalize and be too risk averse.

Always see the big picture of why we’re here. If you are a biomedical researcher, you are here to help people. In the end, it’s about helping patients, helping the human condition and improving human health. You have to follow your heart. I always tell my graduate students, “If you are working on a research project or research problem that doesn’t keep you up at night, then you shouldn’t be working on it.” Feeling that enthusiasm, that excitement, is what drives creativity.

Conversation edited by Suzanne Bowness

News