Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- News & Events

- Recent News

- Alumni Profile: Motorsport medicine pioneer Hugh Scully on the power of a high-performance team

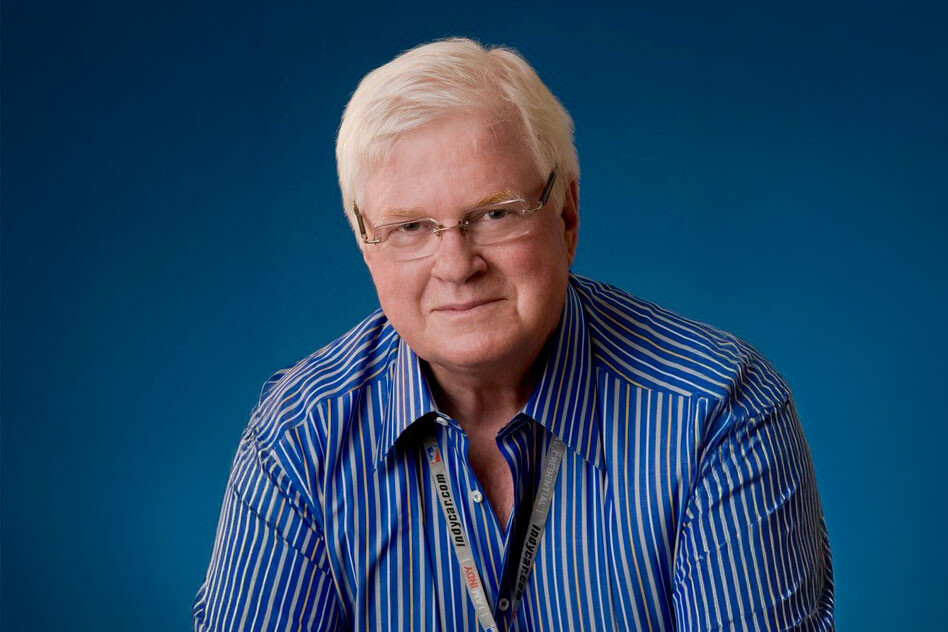

Alumni Profile: Motorsport medicine pioneer Hugh Scully on the power of a high-performance team

Hugh E. Scully (PGME ’70 General Surgery & ’74 Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery) is a professor emeritus of surgery and health policy, management & evaluation at the University of Toronto's Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

He is a former chief-of-staff, trustee and deputy surgeon-in-chief at the University Health Network’s Toronto General Hospital. He is also a past president of the UHN-MSH Physician Funding Group and Academic Medical Organization and continues to serve on the Senate of the UHN Foundation.

Scully was the founding president of the Professional Association of Interns and Residents of Ontario, president of the Ontario Medical Association (OMA), the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS), and chair of past officers of the CMA.

He served on the council of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and on the board of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), and was the only non-American appointed to the ACS Health Policy Advisory Group in Washington. He also served on the board of the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame and represented Canada on the board of the World Medical Association.

Scully has contributed to over 500 peer-reviewed publications on cardiac surgery and health policy, and sponsored and co-authored the book: The Heartbeat of Innovation: A History of Cardiac Surgery at the Toronto General Hospital.

While he has held many health care leadership positions, Scully is particularly celebrated for his impact in motorsport medicine and safety worldwide. The founding president of the Ontario Race Physicians (ORP) based at Mosport (now Canadian Tire Motorsport Park) and the founding medical director/CMO of the Canadian Formula One Race (Mosport and Montreal) and the Toronto CART/Indycar Toronto, Scully is also a founding member (1981-Paris) of what is now the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) World Medical Commission (MEDCOM). He is a founding member and chair emeritus of the International Council of Motorsport Sciences (1988-Indianapolis) and a founding member of the FIA Institute for Motor Sport Safety and Sustainability (2004-Paris).

Scully has received many awards for his contributions to motorsport medicine and safety. In 2000, he was the first physician to be inducted into the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame (CMHF). He was CMHF board chair from 2011 to 2022 and is now chair emeritus. From 2009 to 2024, he was also chair of the CMHF Nominations Selection Committee and continues as the only Canadian member of the American Motorsport Hall of Fame Nominations Committee.

We talked to Scully about his long and varied career, including his pioneering roles in the fast lanes of cardiac surgery and motorsport.

How did you first become interested in medicine?

I knew I wanted to be a physician/surgeon from the age of 12 or 13. My father had not been supported in that ambition, and I was a great admirer of the physician/surgeon father of one of my best friends in Ottawa. The technical challenge and the ability to cure or change the course of a condition with my hands fascinated me.

I did my BA, MD and MSc at Queen's University and then completed my general surgical training at U of T, followed by training in cardiovascular and thoracic surgery (CVT) at U of T and Harvard University (Massachusetts General Hospital).

To this day, I feel that U of T has many of the best postgraduate medical and surgical programs in Canada. My paternal grandfather, my father and mother, one of my brothers and one of my daughters are all U of T grads, so U of T runs in the family!

Originally, I registered for neurosurgery but changed to CVT training after spending time with William “Bill” Bigelow (MD ’56) and his great team of surgeons, nurses, perfusionists and attendants at the Toronto General Hospital.

After my long surgical training, I turned down an offer to join the CVT surgical staff at Harvard and the Massachusetts General Hospital to return to Canada to join Dr. Bigelow and the surgical staff at TGH and U of T. I stayed until my retirement from surgical practice in 2008. I've had a wonderful, challenging and rewarding career in surgery — it was exciting to be part of the many great advances in cardiac surgery over that time! I continue to be involved and active in health policy and teaching.

How did you first get involved in motorsport medicine?

I have always been interested in motorsport. During my general surgical training in the late 1960s, I heard they were looking for doctors at Mosport Park (now Canadian Tire Motorsport Park) near Oshawa. I went with my colleague Herman Hugenholtz (MD ’65, PGME Neurosurgery) to this world-class motor racing circuit to check it out.

It was (and still is) mandated that no motorsport event can be run unless a licensed doctor is physically present at the event. Mosport had an arrangement with three physicians: a family doctor, an obstetrician & gynecologist and a psychiatrist. There was no medical centre, no medical/nursing team, no rescue vehicles or team, and no ambulance(s). It was clear that they needed more help!

Herman and I talked to some of our fellow trainees and nursing colleagues at Toronto General to see if they might be interested in getting involved. Together, we founded the Ontario Race Physicians (ORP), now one of the longest serving race rescue/medicine organizations in the world. I was appointed the founding president.

What changes did you oversee at Mosport?

First, as a team supported by the president of Mosport, Harvey Hudes, we established a Race Medical Centre at the circuit. It was basically a mini emergency room staffed by trauma-trained doctors and nurses. The province would not allow us to have an ambulance on the circuit while an event was running, so we took a couple of pickup trucks and converted them into rescue and recovery vehicles and staffed them with people trained in firefighting and extrication. I also secured insurance for the medical team from the Canadian Medical Protective Association, and I'm happy to report that to my knowledge no physician has ever been sued for their role in motor racing worldwide.

With insurance in place, we convinced the province to allow proper ambulances to be positioned at strategic locations around a circuit to be used once racing was suspended after an accident. We set a standard of 90 seconds for an ambulance to get to an accident — this is still a worldwide standard.

I was also the first in the world to introduce a "medical following car" with an expert racing driver and one or two trauma physicians with intubation skills to follow the racers at the start/first lap of any "standing start" race. It’s still used worldwide today.

How did you get involved with motorsport medicine internationally?

I had been appointed as chief physician for motorsport racing in Canada when I met Professor Sid Watkins, a leading neurosurgeon from the UK, at the Canadian F1 race at Mosport in 1974. He had been appointed the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) medical delegate. We began working together and were invited to a meeting in Paris in 1981 along with four other expert leaders in motorsport medicine (France, Italy, Spain and Monaco). Under the creative leadership of “the Prof,” we founded what would become the FIA World Medical Commission (FIA MEDCOM), now comprised of more than 20 countries. Sid and I became best friends and worked together internationally and with others for 40 years. I continued in various capacities with MEDCOM through 2017.

In 1988, I helped found the International Council of Motorsport Sciences (ICMS) based in Indianapolis (also now comprised of 20 countries), which I chaired from 1994 to 2011 and in which I continue to serve as chair emeritus.

In Paris in 2004, in an initiative created by Bernie Ecclestone and FIA president Max Mosely and led by Sid Watkins, I was a co-founding fellow (and the only Canadian) of the FIA (World) Institute of Motor Sport Safety & Sustainability. This was an integrated organization of motorsport engineers, constructors, senior officials and race physicians doing applied research, planning and successful implementation of many aspects of motorsport safety. The institute was discontinued in 2019 but related research continues.

What have been the most significant developments in motorsport medicine over the last few decades?

In the early 1970s one motorsport racer in seven died each year. Many more were seriously injured, as were many crew members and track personnel. Injury and even death among spectators was also not uncommon.

As FIA and ICMS race physicians, we recognized how important it was to partner with drivers, vehicle and circuit constructors, race organizations and officials, top trauma centres and local/regional/national governments to develop better understanding of their important roles in improving safety in motorsport — which despite advancements continues to be a dangerous sport.

There have been great improvements in driver conditioning and training, driver clothing and position, helmets and visors, car construction, seat belts, fuel cells, deformable components, wheel tethers, "head surround", the head & neck (HANS) device, the HALO (used in F1 and F2 racing) and the Indycar Visor, circuit design (run off areas, safety fence, barrier design), medical/rescue teams, circuit rescue vehicles and ambulances, local medical centres and advanced trauma centre access by either road or air ambulance.

Since 1994, there has been only one mortality in Formula One in racing (in Japan in 2018), qualifying, practice or testing. There has been a significant and continuing reduction in injury and mortality in all aspects of motorsport. The frequency of concussion (TBI) has been reduced by 70 per cent. Much of what has been learned in motorsport vehicles has also been successfully transferred to regular street vehicles.

What do you consider the big highlights in your career outside of motorsport medicine?

My career as an adult cardiac surgeon involved thousands of operations, happily improving and saving many lives. I have had the great privilege of teaching/training many medical students, residents and fellows from Canada and around the world. I am still active in health policy, giving talks on the critical role of physician leaders in developing better models of health care in Canada and internationally, recently as an invited lecturer at Cambridge University in the UK.

But what I am most proud of is having been able to bring different groups together to form integrated accountable teams to improve surgical results, research, cost-effective health policy and teaching — plus safety in motorsport!

I've had the honour and privilege of leading a lot of different teams. Nothing in medicine or other endeavours is a solo effort. You must trust, support and rely on your team. Very importantly, the primary members of your team are your family.

What words of wisdom would you pass on to the next generation of U of T medical students and surgical trainees?

After a complication in the operating room or ICU, or after an accident on a racing circuit, there should always be a team debrief when everyone gets a chance to weigh in. My advice: Do not be afraid to accept constructive criticism and suggestions from others. Recognize and acknowledge if something wasn't done right or could have been done better. You can and will learn from it. That is the strength of a leader. That is the power of a team!

News