Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

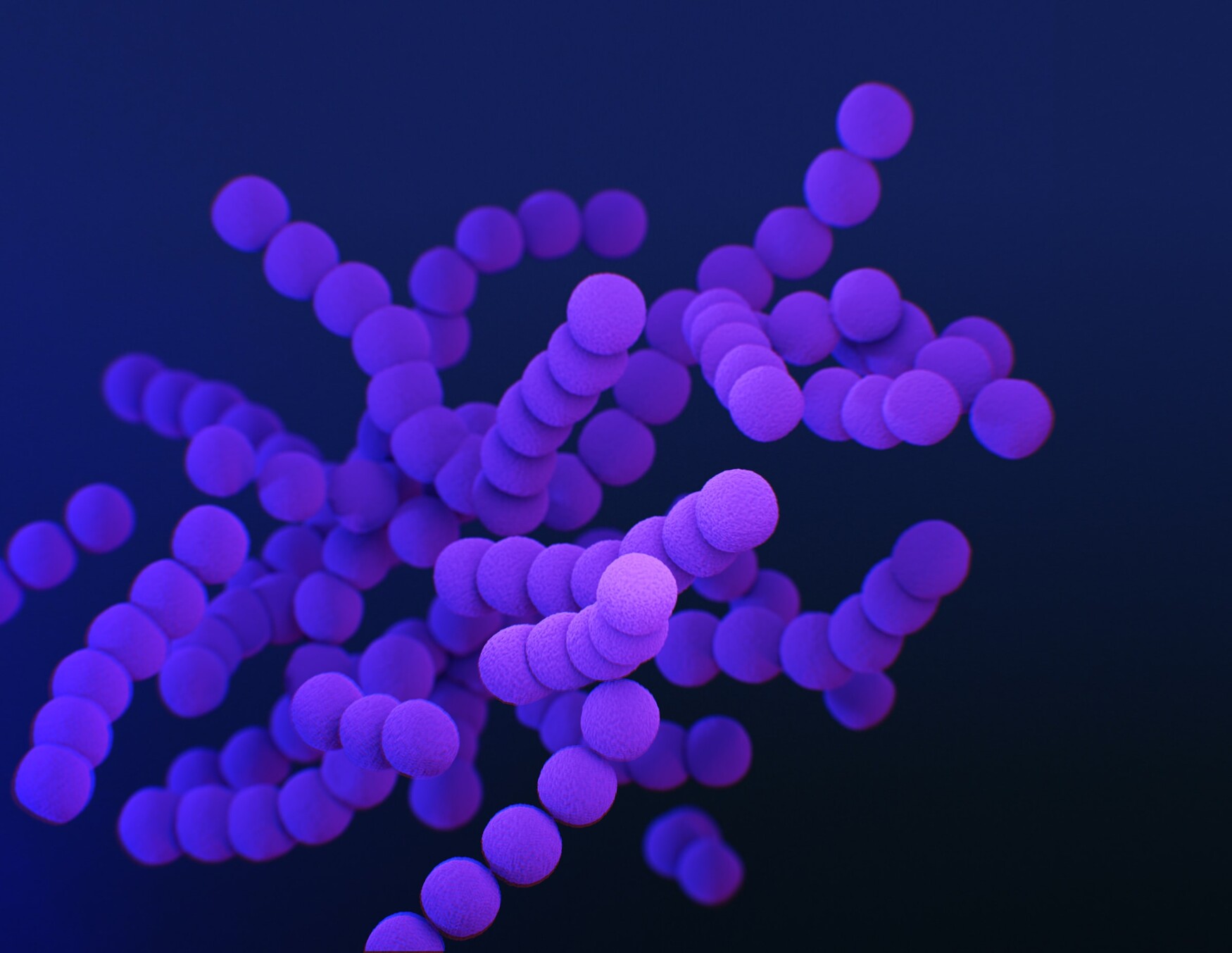

When University of Toronto and Unity Health Toronto medical microbiologist Greg German describes his work advancing bacteriophage (or phage) therapy to a general audience, he keeps his language simple.

“Phages are good viruses that can eat bad germs and superbugs,” says German who, as a medical microbiologist, is a laboratory physician expert and a clinical consultant on infections.

German explains that phages are the most common biological entities in nature. Their ability to destroy bacteria was first characterized by Canadian Medical Hall of Fame scientist, Félix d’Hérelle, in the early part of the 20th century. While phage therapy was initially heralded as a new approach to the treatment of bacterial infections, it was largely abandoned following the widespread adoption of antibiotics in the 1940s.

But, now, with the rising threat of drug-resistant superbugs, the world’s attention is turning back to phages as a possible solution.

“Antimicrobial resistance is an enormous concern,” says German. “Already, millions of people around the world die each year from drug-resistant bacterial infections and the numbers are only growing. By 2050, it’s estimated that more people will die from antibiotic failures than from cancer. The costs, both on a human and financial scale, will be massive if we don’t quickly develop new approaches, like phage therapy.”

New research centres dedicated to harnessing and evolving phage therapies have recently been established in the United States, Australia, Belgium, Israel and France — joining longstanding phage research centres in Poland and the Republic of Georgia. Yet, despite rising global interest in phages, Canada lags behind its international peers.

“Many countries have developed academic laboratories to produce personalized phage therapy for patients who have arrived at a ‘dead-end’ in the treatment of their resistant infections,” says German. “Looking at Belgium alone, scientists there have already treated 150 human patients with phages since 2000. But, here in Canada, we’ve done so only twice during the same period.”

It’s a shortcoming German and a small, but dedicated, network of phage therapy researchers across the country are attempting to overcome — an effort that will now be strengthened and accelerated following a recent $5-million gift from an anonymous donor to U of T’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

The gift will fund a number of initiatives tied to phage therapy, including the creation of a new professorship in bacteriophage therapy research and innovation at Temerty Medicine, expanded Canadian bacteriophage biobanking resources, as well as the establishment of a bacteriophage therapy research accelerator fund that will provide grants to high-impact phage therapy studies throughout Canada.

“This gift is one of the largest, if not the largest, gifts ever made in support of phage therapy and will give Canada a huge boost in the race to fight superbugs,” says German, who is currently leading a single-patient phage therapy clinical trial for the treatment of a drug-resistant, chronic urinary tract infection. “It is a tremendous investment in the leadership, ideas and infrastructure needed to take Canadian phage research to the next level.”

The demand from Canadian clinicians and patients who have exhausted all other options for the treatment of their resistant infections is already there — and it’s only expected to grow"

German also sees the donation setting the pace for other giving and grants necessary to realize the full breadth of his vision of a new era Canadian phage therapy.

“Our ultimate goal is to establish Toronto as the country’s premiere phage therapy centre of excellence,” he says. “The demand from Canadian clinicians and patients who have exhausted all other options for the treatment of their resistant infections is already there — and it’s only expected to grow. But right now, our impact is limited. A new, centralized hub would drive domestic phage therapy research and innovation, as well as generate Canadian-made phages.”

“Temerty Medicine’s unmatched size and depth of expertise, as well as U of T’s strong track record of collaboration with other institutions, makes us uniquely well-positioned to deliver cutting-edge advances in translational health science, like phage therapy,” says Trevor Young, Temerty Medicine’s dean and the vice-provost, relations with health care institutions at U of T. “We’re so grateful for this gift which will fuel our talented phage researchers as they work to address a looming challenge to the health of people and communities everywhere.”