Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- News & Events

- Recent News

- Dr. Wayne Carman: Investing in Plastic Surgery Research

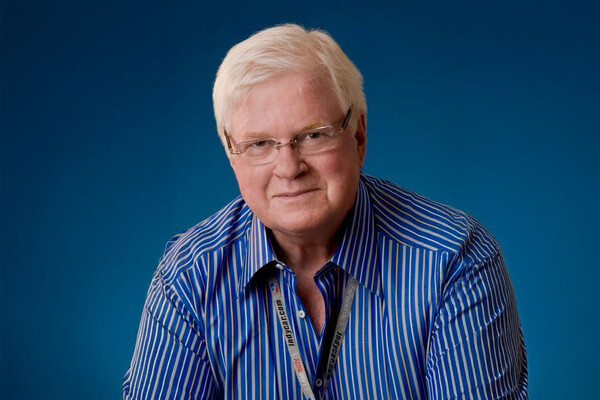

Dr. Wayne Carman: Investing in Plastic Surgery Research

Dr. Wayne Carman [BSc ’72, MD ’75, MSc ’79, FRCSC ’82 (Plastic Surgery)] is the former Chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery at The Scarborough Hospital and also served as the Director of the Scarborough General Hospital Burn Unit. He was President of the Canadian Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (CSAPS) and is the Secretary-Treasurer of the Canadian Association for the Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (CAAASF). He founded and maintains his own private clinic, the Cosmetic Surgery Institute, in midtown Toronto.

Dr. Carman has the distinction of being one of the first people to graduate as a surgeon scientist in the Faculty of Medicine. This fall, Dr. Carman established the endowed Dr. Wayne Carman Surgeon Scientist Trainee Award as a way to both help advance his field and to honour a fulfilling career.

“Let’s face it, economic realities on the academic side always exist — there are never enough resources, so I think if you have the opportunity to mitigate that a little bit, it’s fulfilling… it underscores the commitment I have to furthering plastic surgery research.”

Dr. Wayne Carman [BSc ’72, MD ’75, MSc ’79, FRCSC ’82 (Plastic Surgery)] has had a rewarding career in both the private and community spheres. He enjoys running a private practice and maintains an appointment at the Scarborough Health Network. Dr. Carman recently spoke with Director of Alumni Relations Sara Franca about the field of plastic surgery, his gift to the Department of Surgery — and reflected on some of the more memorable moments of his career.

What made you choose to pursue medicine in school — and what is it about the area of plastic surgery, in particular, that appeals to you?

I knew I wanted to go into medicine, that was an early decision. There are no other medical people in my family, but I liked the idea of it, the scope of it — the problem solving and the personal interaction.

I always leaned toward surgery. I have always been more of a hands-on person, and I felt the manipulative aspect of surgery was appealing — the dexterity and the challenge of the physical part. I then needed to narrow that down, and plastic surgery came into the mix. I felt early on that plastic surgery was one of the more interesting fields. It probably had the most scope for original thought and creativity — we operate on all parts of the body and the problems are frequently unique.

I also recognized many branches of medicine are mainly diagnosis related. This is a valuable aspect of medicine, but in most medical specialties, the greater part of one’s energy is spent determining what is wrong with somebody and treatment often is the lesser part of the exercise. I found plastic surgery to be the exact opposite — the diagnosis is generally obvious — most of your energy is focused on fixing the problem. I felt a clinical field, which placed more emphasis on problem management, would be the most satisfying career choice.

While you were in school, were there any specific colleagues or faculty members who made an impression on you?

I pursued the idea of plastic surgery starting in medical school and met Dr. J. F. (“Jim”) Murray (MD ’43) who became a mentor. He was the pre-eminent hand surgeon in Toronto back then, and hand surgery always appealed to me as a sub-speciality. We did research projects together, I spent some elective time with him, and worked with him during my residency — I learned a lot from Jim.

How did you feel about pursuing a graduate research degree during residency?

During my residency, I decided to get more involved with the research side. I took an extra year and did basic science research, where I had an animal model and I did surgical research on flexor tendon healing — that’s where I received my Master’s degree. I think I was one of the first to have done that at U of T. Others had done research, but they hadn’t pursued the degree part of it and defended a thesis.

The advantage of this training was it fostered a more detailed appreciation for what research involves, the structure of a research study, the shortcomings, the advantages, how to facilitate a conclusion based on research. You really learn to be critical of scientific papers and articles, and you develop a more systemized approach to problem solving, which carries over into your clinical practice. It’s easier for patients to understand your treatment rationale when you can substantiate your conclusions.

You have established an endowed scholarship for surgeon-scientist trainees in the Division of Plastic Surgery — what inspired you to do this?

The idea of giving back. I’ve been doing this work for decades — and you think, ‘now what?’ Plastic surgery is something that defined most of my life and so it makes sense for me to do something that speaks to that. And let’s face it, economic realities on the academic side always exist — there are never enough resources, so I think if you have the opportunity to mitigate that a little bit, it’s fulfilling. It just kind of underscores the commitment I have to further plastic surgery research. At this point in my life and my career, it seems appropriate. I appreciate the work academics do, and I don’t want to lose that connection to the Department.

My scholarship helps to facilitate funding for those who are interested in research, and when an award is presented to a recipient, there is a connection between the person who receives it and person who donated it. You get to say, “Hi, I was in your place many years ago. I know how it feels.”

What advice would you have for current trainees pursuing plastic surgery?

You need to make sure what you end up doing is what you really like to do — don’t be pressured by circumstances or popular trends. The other thing is you shouldn’t narrow down your focus too early during training. You need to have a broad appreciation of the field of Plastic Surgery. If you don’t have a broad clinical exposure, your creativity is limited. From a practical point of view, more diverse training also gives you a greater range of job opportunities and more flexibility to choose where to locate your practice. Until you have some exposure to the broader range of what we do, it’s hard to decide what you might really like. Narrowing down is best left to later in your residency years.

Could you share some of the more memorable surgeries of your career?

I think the cases that are most memorable are those dealing with trauma. Trauma cases arise in an instant and your ability to assess the problem and devise a treatment plan must be done in the moment. It’s a challenging exercise. Specific injuries can be memorable — a dog bite to a child’s face, a worker who put his hand into a printing press — you can imagine. Thankfully, you don’t see these problems every day, but I think that being able to restore somebody who has had a traumatic injury and get them back as close as possible to how they were before is probably one of the most challenging and satisfying things that we do.

News