Main Second Level Navigation

Breadcrumbs

- Home

- News & Events

- Recent News

- Dr. Ronald Zuker, MD’69, PGME’76

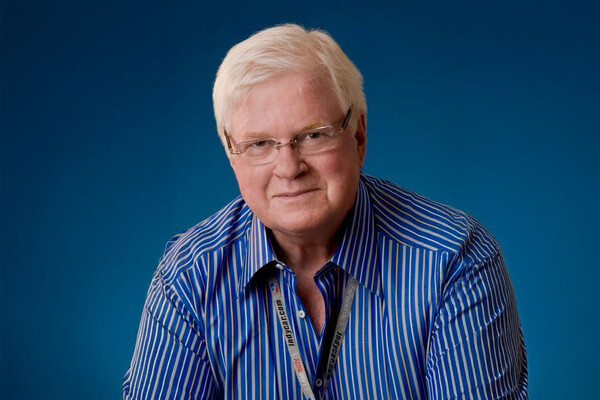

Dr. Ronald Zuker, MD’69, PGME’76

Dr. Ronald Zuker, MD’69, PGME’76 – a paediatric plastic and reconstructive surgeon – is the worldwide authority in facial reanimation. Together with Dr. Ralph Manktelow, he performed Canada’s first successful muscle transplant to correct facial paralysis. He has a major interest in the management of cleft lip and palate, and serves on the Plastic Surgery Council of the International Volunteer Organization “Operation Smile.” He also directs and coordinates the Educational Exchange Program between SickKids and The Guwahati Comprehensive Cleft Care Centre in Assam, India.

Dr. Zuker was the Medical Director of the SickKids Cleft Lip and Palate Program for over a decade. He served as Chief of the Division of Plastic Surgery at SickKids from 1986-2002. He is the past chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics (Section of Plastic Surgery), Past President of the American Association of Pediatric Plastic Surgeons, and Past President of the American Society for Reconstructive Microsurgery. He is very active in teaching and training future reconstructive surgeons.

In January 2016, Dr. Zuker was part of an 18 member University of Toronto team that performed Canada’s first arm transplant, a project which Dr. Zuker initiated five years previously.

Collaboration has been the key focus of my career.

What have you been up to since graduation? Step us through your career a little bit.

After graduation I did a rotating internship at the Vancouver General Hospital. I knew that I was interested in surgery – I was always a hands-on kind of person – and I had always wanted to work with children. During my internship I was fascinated by the ability to change people’s lives with surgical intervention and be able to envision new procedures and new ways of advancing the field. I realized that to do really interesting pediatric surgery there are very few places to do that; you have to be in a major institution.

When I finished my internship I came back to Toronto and I was in family practice for several months. Then I got a job in Peru in the Amazon basin working with the Shipibo-Conibo people. My job was to build a dugout canoe and go up the river for two weeks with a native river guide and another native person who wanted to become a sanitario; a medical person for his community of about 50 people. We would go up river for two weeks and visit native villages and hold clinics, do some vaccinations and other public health improvements, and then I would come back to the hospital to work a few shifts in anesthesia. I would then head the opposite direction for a couple of weeks visiting villages. I did that for a year and found it an absolutely wonderful experience. Importantly, it gave me a chance to think about my career. When I came back I had decided I wanted to do plastic pediatric surgery and be a part of this innovative new field: microsurgery.

I was able to get a McLaughlin fellowship which allowed me to travel to centres I felt were most advanced in microsurgery and in pediatric surgery. At the end of ’77, I returned to Toronto to start my practice. I was very excited to be at Sick Kids. I also had an appointment in the adult program to do microsurgery, at that time it was located at St. Mike’s. Dr. Ralph Maketelow and I built up parallel microsurgery practices in both the adult community and the pediatric community; assisting each other at St. Mike’s and Sick Kids. These cases are very difficult to do on your own, it’s not sustainable to do for your entire career but Dr. Manktelow and I did it together so rather than having a very long and difficult day, we would have a fairly relaxing day that we could bounce ideas back and forth and help each other and work together. That made it possible for us to work at this level for 30 years.

How has your career path been defined by your experience at U of T?

I’ve been very fortunate to see the emergence of the subspecialty of microsurgery. There are many places in the world that didn’t think this field was worthwhile or that it was too resource intensive, but U of T supported my vision that microsurgery would indeed be something that the reconstructive world would need.

Microsurgery is the putting together of very small blood vessels and nerves under the microscope. It enables us to do things that we could not do without that technology. For example, if somebody cuts their finger off, we can sew the artery and the nerve together under the operating microscope and the finger will survive. In the late 70’s and early 80’s that was just emerging as a technical possibility with the development of appropriate microscopes and micro-instruments. We were able to put together a program at U of T that became really quite influential in the whole microsurgical world. At Sick Kids in particular we established a program that focused on new developments in hand surgery, facial reconstruction and facial reanimation.

The main area where I have been involved with both children and adults is facial paralysis, which affects the controls of the eye and the mouth and secondly facial animation, like a smile. The treatment options available prior to microsurgery weren’t very good. They might give some symmetry to the face, but they never allowed for any movement. With microsurgery, we were able to move muscles around; reconnect the blood vessels and reconnect the nerves so that the muscles move and function in a new location. I learned this technique in Japan, but we took that concept and refined it and changed it a lot here in Toronto. My colleague Dr. Ralph Manktelow and I changed a number of different approaches as to how we could engineer the muscle in a better physical composition, make it smaller so it wasn’t too bulky, transplant it and make it work with a new motor nerve. That’s what we became most well-known for here in Toronto in the microsurgical realm; facial paralysis reconstruction.

None of this could have been done without the supportive setting that the U of T provided during those early days.

Can you describe a typical day at work?

Every day is a little bit of a surprise, you never know what’s going to walk through the door or what difficulties you’re going to encounter and that’s what makes it exciting. You see cases and situations that you’ve never seen or even heard of before and you have to rely on your experience and ingenuity to figure out how to treat or manage a particular condition. Fortunately we have all the help in the world at this institution, with every subspecialty available for consultation and collaboration. Collaboration has been the key focus of my career.

U of T undeniably creates an atmosphere of collaboration, and so does our Canadian healthcare system and the hospital network where we work closely with each other. We don’t have a competitive, knock-the-other-guy-down culture here. Because of this, we’re able to work together and set up divisions with specialists and sub-specialists to support one and other – otherwise we couldn’t bring things forward working independently and fighting against one another. U of T has been instrumental in facilitating the collaboration.

What has been the highlight of your career so far?

I’ve had several awards from different organizations, but the biggest one for me was the lifetime achievement award from the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons which I received a year and a half ago. That was really a highlight because it was from my peers who have known me and my work for 30 years and they recognized my achievements. That was a big one for me.

What words of wisdom of you have for current U of T students?

One of the major things that I have learned over the years is that progress is made by different disciplines working together. I’ve been part of many innovations that could never have happened without this environment of collaboration where we can communicate and work together. I can tell someone what my capabilities are and they can tell me what their problems are and we work together.

So for the students; try not to work in a little silo on your own. Work together in a collaborative fashion with other people. You can go further working together than you can on your own.

News