Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

Lloyd Rang

One day in 2011 when Sacha Agrawal was a Psychiatry Fellow at Yale, he read in the curriculum that he had the option of teaming up with a patient, who would act as an advisor. When he asked his program director about it, she told him no one had ever done that before.

One day in 2011 when Sacha Agrawal was a Psychiatry Fellow at Yale, he read in the curriculum that he had the option of teaming up with a patient, who would act as an advisor. When he asked his program director about it, she told him no one had ever done that before.

Meanwhile, at the University of Toronto, Psychiatry resident Laura Lachance was meeting with a group of her colleagues at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). The informal group — the Resident and Consumer Initiative (RACI) — got together regularly with former patients to talk about ways to improve the Psychiatry curriculum.

Little did they know that in a few years, they would both take part in a bold new initiative at the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine. The “Client as Teacher” program pairs Psychiatry residents and people recovering from mental health and addiction issues to help the residents better understand how people experience recovery

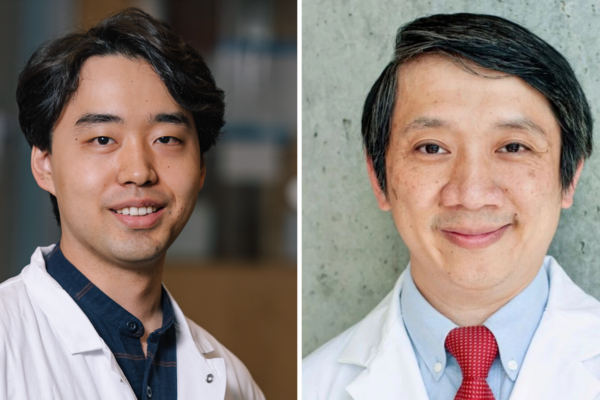

“Patients are often objects of study,” says Agrawal, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry. “Students come in and examine them to learn about symptoms and signs of disease or improve some clinical skill. The people they are examining often play a passive role in health professions education. We want to radically transform that role to one that is active and powerful.”

This radical transformation led Agrawal to join with Pat Capponi, a long-time consumer-survivor advocate, to build a six-month long course for fourth-year Psychiatry residents that inverts the doctor/patient power dynamic. Residents are matched with someone who is well on their way to recovery. They meet six times to discuss how service users experience everything from hospital admissions, to doctors visits, to recovery at home.

“Trainees’ experiences of people in the system is often skewed. They typically encounter people when they are in crisis,” says Agrawal. “Things like how people cope with prejudice and discrimination both inside and outside the health care system, how they repair relationships, how they heal their self-esteem and generally put their life back on track — these are important parts of a person’s recovery that trainees don’t often learn about.”

That same desire to better understand what people with mental health and addiction issues go through was the inspiration behind RACI. At first, the goal of the group was simply to bring together service users and residents over dinner to get to know each other better, but it quickly evolved into something bigger.

“People were voluntarily getting together as RACI before I came along,” says Lachance, who is now the Co-Chief Resident at CAMH and now one of the more senior members of RACI. “It’s provided all of us with a better sense of the social determinants of health and the patient experience from illness to recovery. Personally, I’ve learned a lot about what it’s actually like to visit a psychiatrist across settings, and RACI has helped me to question why and how I do things, which hopefully continues to improve the quality of care I deliver.”.”

“The most important part of the course for residents is that they get a better sense of what ‘recovery’ means from a first-hand perspective,” says Agrawal. “It helps them understand what it is like to go to the emergency room, or be involuntarily admitted — and shows them that recovery is possible.”

Now that the “Client as Teacher” program is officially part of the curriculum, the future of the grassroots RACI group is a little less clear.

“I still think there’s value in bringing people together,” says Lachance. “The nice thing about RACI is that you don’t have to wait until fourth year to join. Having real, personal encounters with mental health system users is a really positive experience for most residents and I think the earlier we can do it in our training, the better we will be as doctors.”