Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

For certain operations, surgeons are able to operate from a distance. They use specialized tools – a long tubular device combined with surgical equipment and video technology — that allow them to access internal organs and structures through a small incision, and then to operate while “seeing” what they’re doing from afar. This minimally invasive technique, known as endoscopic surgery, has huge advantages: lower risk of bleeding, less scarring, quicker recovery. But although surgeons are able to see the surgery, they aren’t always able to “feel” it. A new start-up is setting out to change that. Faculty of Medicine writer Carolyn Morris caught up with SensOR Medical Labs co-founder Robert Brooks to find out more.

What is this device, and how will it help surgeons “feel” from afar?

What is this device, and how will it help surgeons “feel” from afar?

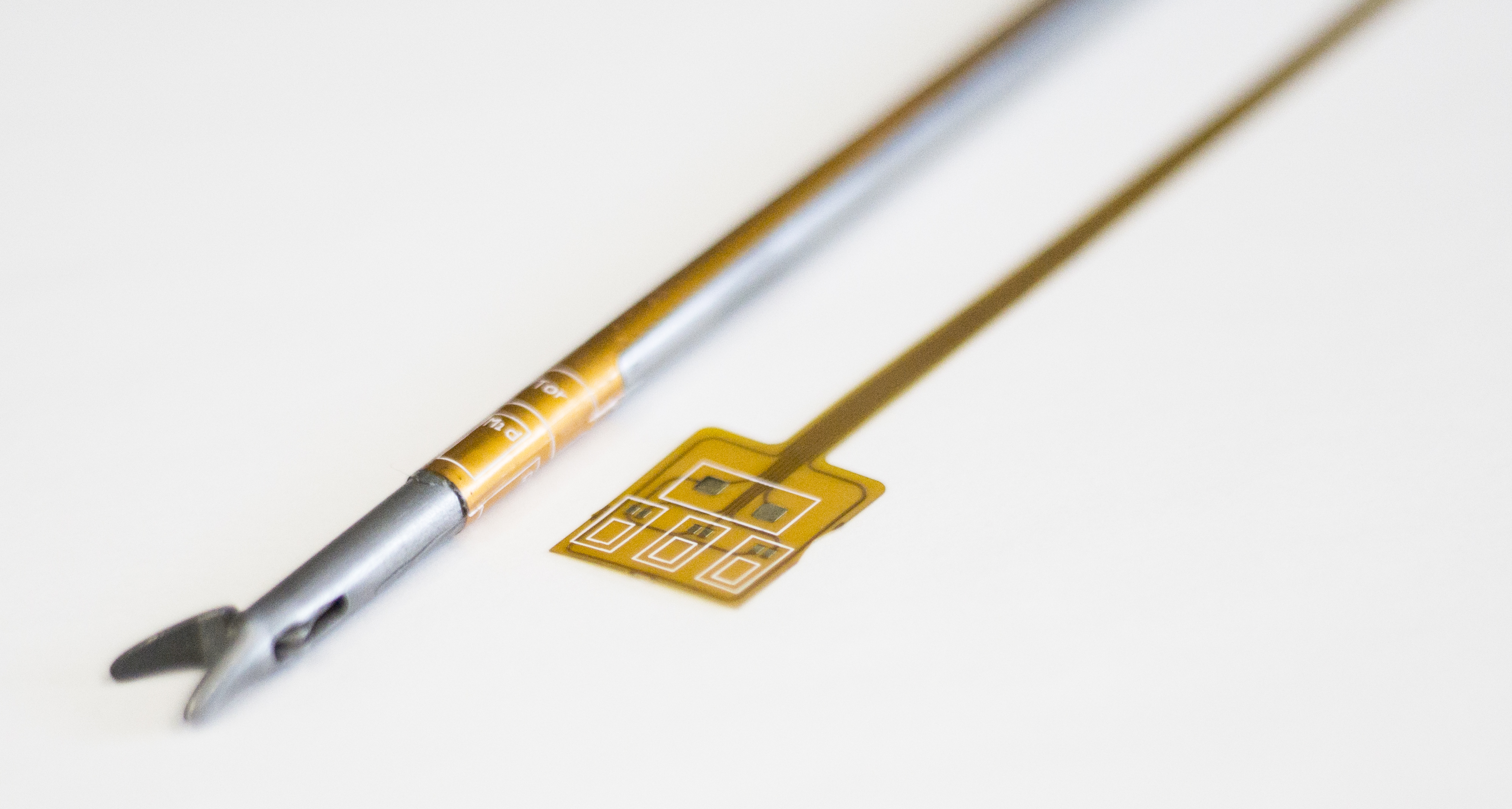

The device is a force-sensing skin that wraps around endoscopic tools and measures the force surgeons are applying to the tissues within the body. It’s very difficult to accurately judge this force in endoscopic surgery. And current endoscopic surgical training only evaluates speed and accuracy, while proper force control is essential to suture tying and tissue manipulation. Using too much or not enough force can cause leaks, necrosis, excessive scarring, and additional post-operative pain.

By giving endoscopic tools the ability to sense the force they’re applying to tissue, we’re effectively allowing the surgeon to feel what they’re doing from outside the body. Not only will it reduce surgeon training time for new surgeons, it will also reduce complications, scarring, and post-operative pain and improve outcomes for patients.

How did you get the idea for this?

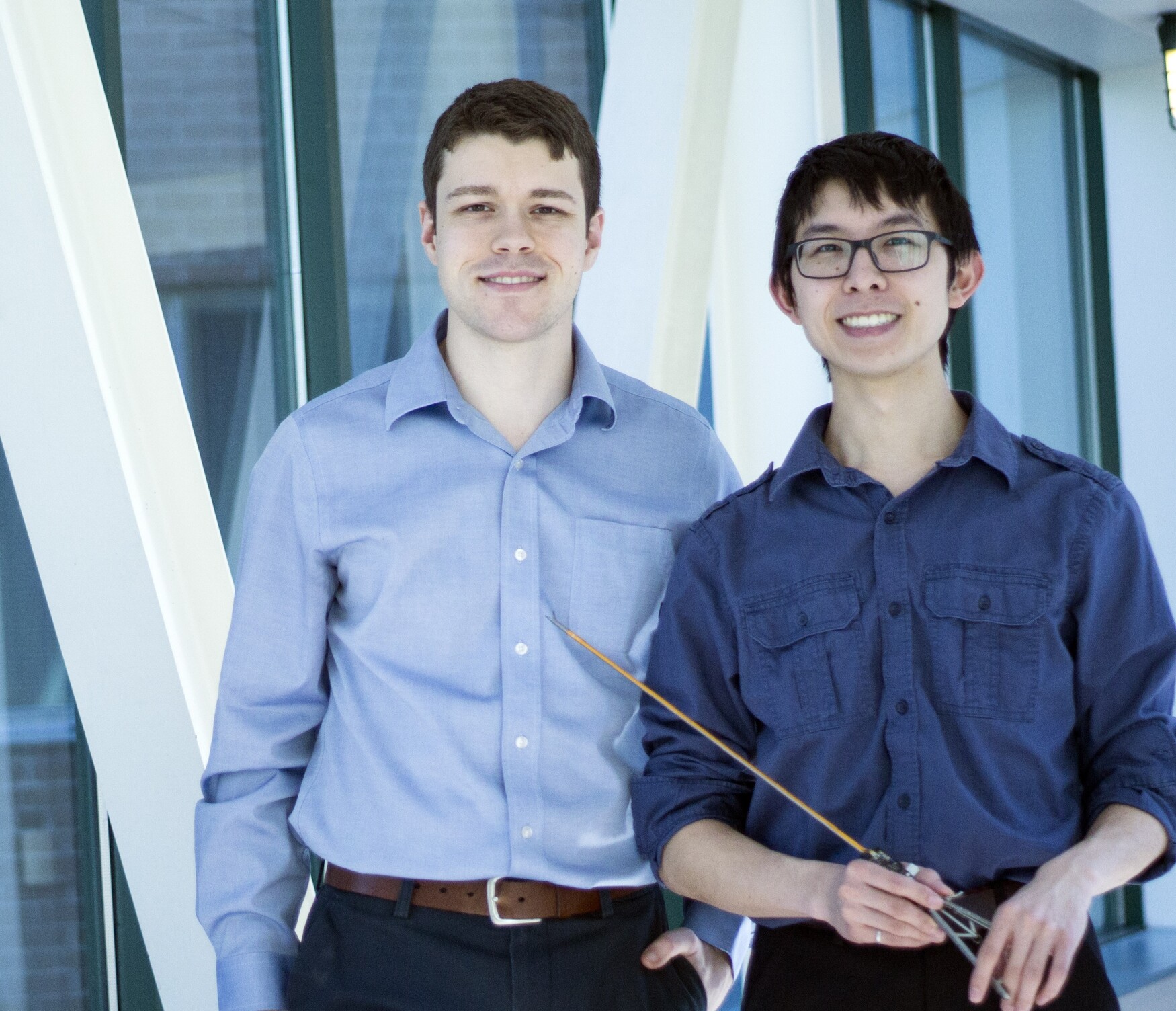

My business partner Justin Wee and I both work in the same lab – the Center for Image Guided Innovation and Therapeutic Intervention (CIGITI) at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). I did my PhD in Mechanical Engineering at the U of T, and Justin was doing his PhD at the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering. His PhD supervisor Professor Ted Gerstle, a general surgeon at SickKids, told him how training for endoscopic surgery only evaluated speed and accuracy in tying sutures — but they really needed a way to teach and measure force.

When Justin and I brainstormed ideas, we compared this with other industries — looking at a suture as a fastener. In everything from aerospace to construction, force sensing and control is widely used and, in some cases, mandated. It makes sense that if you wouldn’t get on a plane that wasn’t assembled with force-sensing tools then you shouldn’t be performing surgery without force-sensing tools either. So we started developing the device at CIGITI.

What response and support has your project gotten so far?

At first we thought this was just going to be a small innovation that could help trainees learn suturing in general laparoscopic surgery. But when we started talking to other surgeons, and doing a literature review, we realized there was a broader need for this. For example, in neuroendoscopic surgery it’s crucial to not apply too much pressure to sensitive brain tissue. And even experienced surgeons can benefit from “feeling” how much pressure they’re applying.

We’ve gotten a lot of support through our lab at CIGITI, and the Faculty of Medicine’s Health Innovation Hub (H2i) has helped us transition the project from research to a commercially viable product. I’ve also been granted the University of Toronto Heffernan/Co-Steel Innovation Commercialization Fellowship to develop this project full-time. The team has also recently received the Banting and Best Commercialization Fellowship and will be joining the Faculty of Engineering’s 2016 Hatchery Cohort.

Professor Gerstle, who originally inspired the project, has been closely involved in the development as well as encouraging commercialization. We’ve also gotten a lot of support from Professor James Drake, a surgery professor and the head of Neurosurgery at SickKids. Thomas Looi, a PhD candidate at the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering and a Rotman MBA and Engineering Science Alumni, has been our management advisor and a strong proponent of the commercialization effort.

What are the next steps?

The force-sensing skin has been accepted for its first publication in the ASME Journal of Medical Devices and at the Design of Medical Devices Conference this April. And earlier this year SensOR won the National Business and Technology Conference’s 2016 Veteran Entrepreneurship Pitch Competition.

We’re going to be opening up beta units for purchase by researchers, medical schools, and teaching hospitals late this summer.