Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

Research from Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and the University of Toronto has pinpointed three sub-groups of people in their early 60’s who have an observable risk for dementia that they and their clinicians can still do something about.

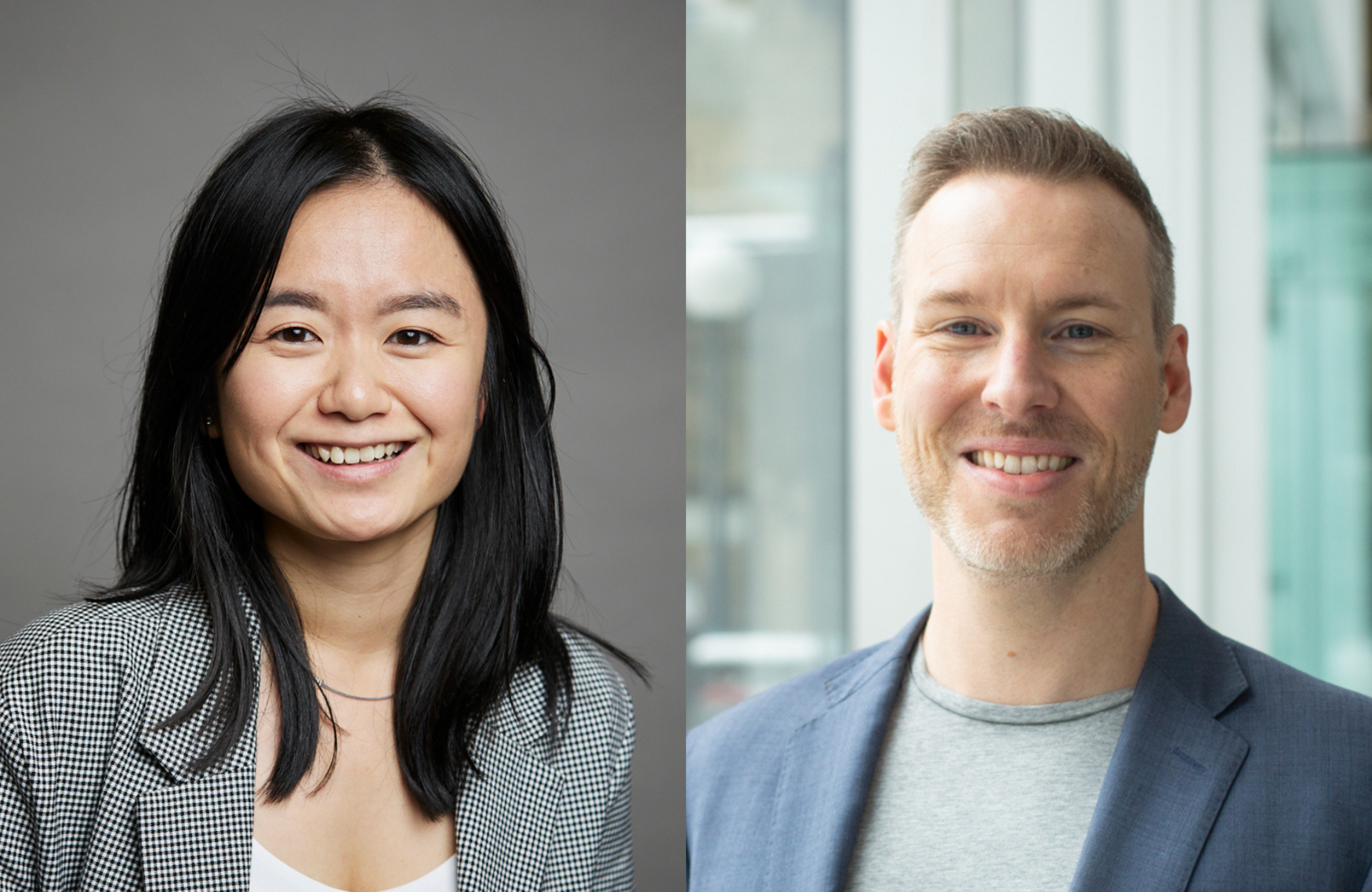

“The findings from this study may help to better predict an individual’s risk in order to plan a personalized prevention strategy to slow down the onset of dementia,” says Lisa Xiong, lead author of the study and a PhD candidate in the department of pharmacology and toxicology at U of T’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

In 2020, the Lancet Commission identified 12 modifiable factors that increase population-level dementia risk: low education, hearing impairment, traumatic brain injury, hypertension, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, smoking history, depression, social isolation, physical inactivity, air pollution and diabetes. It was unclear if these risk factors co-occur among individuals in a way that could help clinicians spot people who may need extra attention.

“We aimed to describe the different ways in which individuals develop dementia by identifying underlying profiles, or subpopulation groups, based on the Lancet Commission’s modifiable risk factors, and we found them,” says Xiong, who is a researcher at the Dr. Sandra Black Centre for Brain Resilience and Recovery at Sunnybrook Research Institute.

The researchers used data from the UK Biobank, an observational study of over 500,000 participants living in the United Kingdom, to identify subgroups of people based on their modifiable dementia risk factors in dementia-free adults who were aged 60–64 years at the start of the UK study.

They then analyzed over 15 years of follow up data from these participants to examine their risks of developing dementia.

The study, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, showed three distinct “risk profiles” related to cardiometabolic (heart health) risk, substance use-related risk and a low-risk category of people who had fewer of these risk factors for dementia.

“Understanding how these distinct combinations of factors together drive dementia allows for a more personalized, or a more person-centered approach to, risk assessment and may lead to targeted strategies for prevention and treatment,” says Walter Swardfager, senior author of the study and an assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology at Temerty Medicine.

The researchers also used the results of cognitive tests and brain imaging to understand how the risk profiles set the stage for dementia. The cognitive tests revealed that people with distinct risk profiles performed differently on brain function tasks such as thinking, learning, remembering and using judgement and language, while brain imaging showed variable amounts of brain shrinkage and damage to the white matter.

“The three risk groups showed unique characteristics on both brain imaging and cognitive testing, showing how individuals can be at risk for developing dementia in different ways,” says Swardfager, who is also a scientist in the Hurvitz Brain Sciences Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute.

The researchers also showed that some characteristics of the three profiles differed between sexes and that interactions between these profiles and their genetic susceptibility for Alzheimer’s disease influenced dementia outcomes. Up to half of people’s dementia risk is based on their genes, reflecting an important contribution that can be inherited from parents.

“The study illustrates how complex interactions between genetic and modifiable risk factors for dementia manifest in traits that we can observe many years before dementia develops, providing a new opportunity to modify the disease trajectory,” says Swardfager.

The authors advocate for further development of these dementia risk prediction tools to advance personalized risk assessments and precision medicine approaches, including a need to examine multi-domain dementia risk in different racial and ethnic groups.

The research was a collaboration among Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, the University of Toronto, Ottawa Heart Institute, University of Ottawa, Østfold University College (Halden, Norway) and Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (UHN).