Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

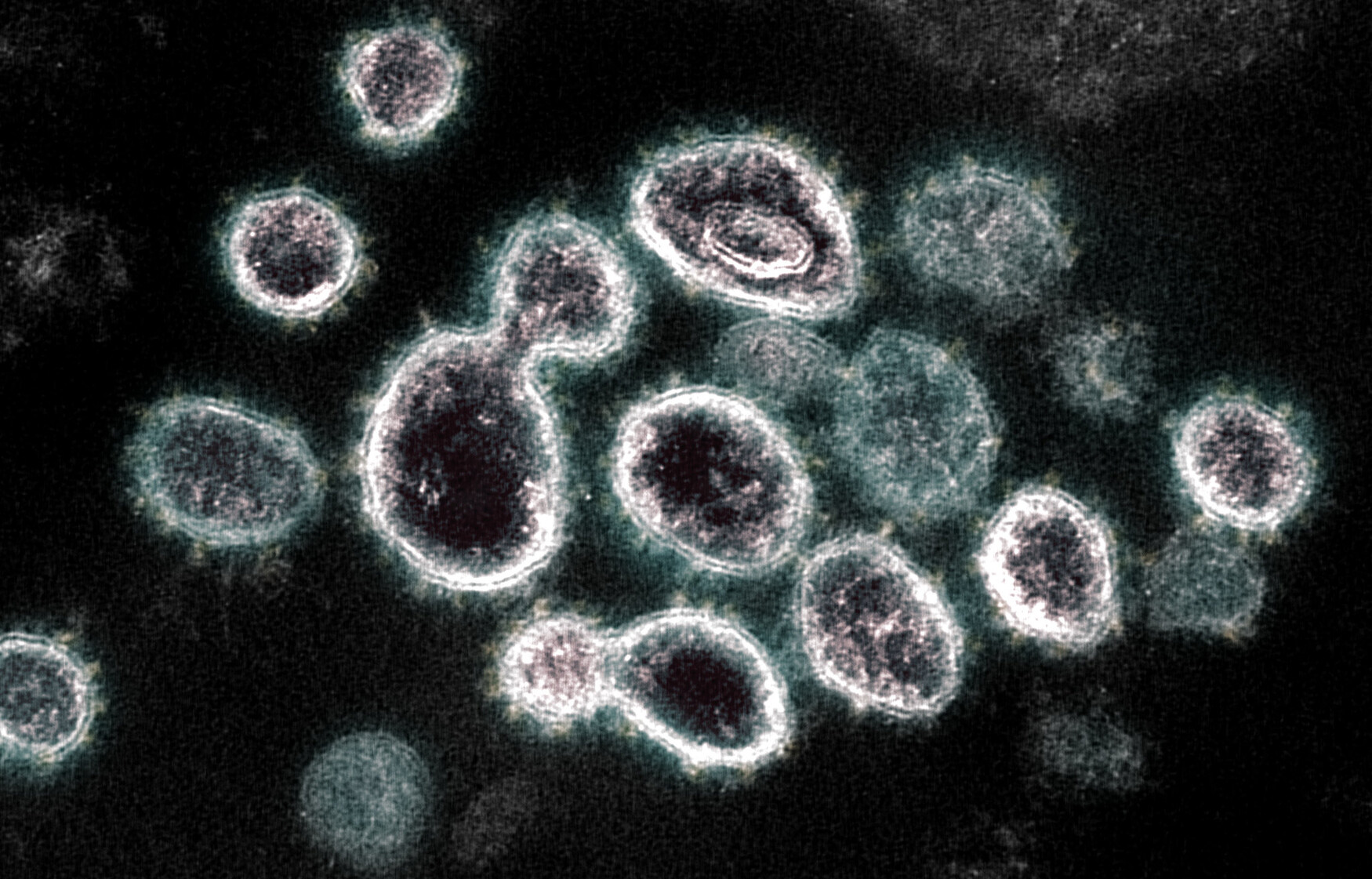

More than four years after the COVID-19 pandemic began, the disease is very much still among us. Recent estimates suggest that about one in every 47 Canadians are now infected with SARS-CoV-2.

And, despite huge advances in our understanding of COVID-19, there is much more to learn. We do know that following infection, it’s critical for our cells to make new proteins to defend against the virus that causes the disease.

Talya Yerlici, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine, is the first author on a recent paper that details how SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the manufacture of proteins.

We spoke with Yerlici, who is based in the lab of Professor Karim Mekhail in the department of laboratory medicine and pathobiology, about the findings.

What have you discovered about how COVID-19 uses proteins?

One way SARS-CoV-2 makes us sick is by using a strategy called ‘host shutoff.’ This means that while the virus makes copies of itself, it also slows the production of vital components within our cells. As a result, our bodies take longer to respond to the infection.

When SARS-CoV-2 enters our cells, it disrupts the process of making proteins, which are essential for our cells to work correctly. A particular SARS-CoV-2 protein called Nsp1 has a crucial role in this process. It stops ribosomes, the machinery that makes proteins, from doing their job effectively. The virus is like a ‘clever saboteur’ inside our cells, making sure its own needs are met while disrupting our cells’ ability to defend themselves.

We found that Nsp1 is good at blocking ribosomes from making new proteins, but also interferes with the production of new ribosomes. In effect, it shuts down the machinery output, and the ability to make the machinery itself — a serious double hit.

It does this by blocking the maturation or processing of specialized RNA molecules needed to build ribosomes. This adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of SARS-CoV-2's interference with the host cell.”

How could this discovery impact treatment for those with COVID-19?

Building on our published research, it will be crucial to understand how Nsp1 works to stop different types of human cells, tissues and organs from making proteins when infected with different variants of SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses.

Scientists have been working to find precision medicines that can counteract Nsp1 and help fight against the continually evolving SARS-CoV-2 virus. These drugs aim to help infected cells keep producing proteins and build a robust immune response when dealing with infection. Ongoing research on such drugs should now benefit from testing whether they can block Nsp1 from interfering with both the production and function of ribosomes, and this should help find more effective precision medicines.

How did you start and pursue this line of research?

This project started because of circumstances during the COVID lockdown. We wanted to help in the fight against the pandemic. However, since I couldn't physically work in the lab, we took the opportunity to analyze next-generation sequencing datasets computationally from home.

Looking at published RNA-sequencing datasets, we realized that cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, compared to uninfected cells, may have difficulty processing the RNA molecules needed to build ribosomes. Through this analysis, together with Dr. Mekhail, we developed hypotheses and designed the project.

I had the privilege of collaborating closely with the talented members of the Mekhail lab, Alexander Palazzo’s group from the department of biochemistry at Temerty Medicine, and Brian Raught and Razqallah Hakem’s labs at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. This work wouldn't have been possible without the collective efforts of our team and collaborators, and I’m grateful for their contributions. My responsibilities included conducting numerous hands-on experiments and bioinformatics analyses, analyzing the results, and preparing the paper for peer review and publication.

What were the most challenging and rewarding aspects of this project?

The most challenging part was conducting research during a global pandemic, which presented many logistical hurdles, from disrupted lab routines to limitations on collecting and using samples infected with SARS-CoV-2.

On the other hand, the opportunity to contribute to our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 viral mechanisms and shed light on potential therapeutic targets was incredibly fulfilling. Seeing our research culminate in a published paper and knowing it could inform future strategies for combating coronaviruses is deeply gratifying.

What are your longer-term goals, as a scientist?

As an independent investigator in my future lab, I want to study how the complex processes of making ribosomes affect the body's natural defense against viruses. It's an area I find compelling and presents ample opportunities for further exploration. One approach I’m particularly interested in is integrating RNA-sequencing with genetic CRISPR and small-molecule chemical screens, targeting distinct stages of ribosome biogenesis across diverse infection or infection-mimicking conditions. Such integrated approaches hold promise for uncovering novel mechanisms underlying the regulation of antiviral responses and should help us find innovative and impactful ways to fight viral infections.

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.