Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

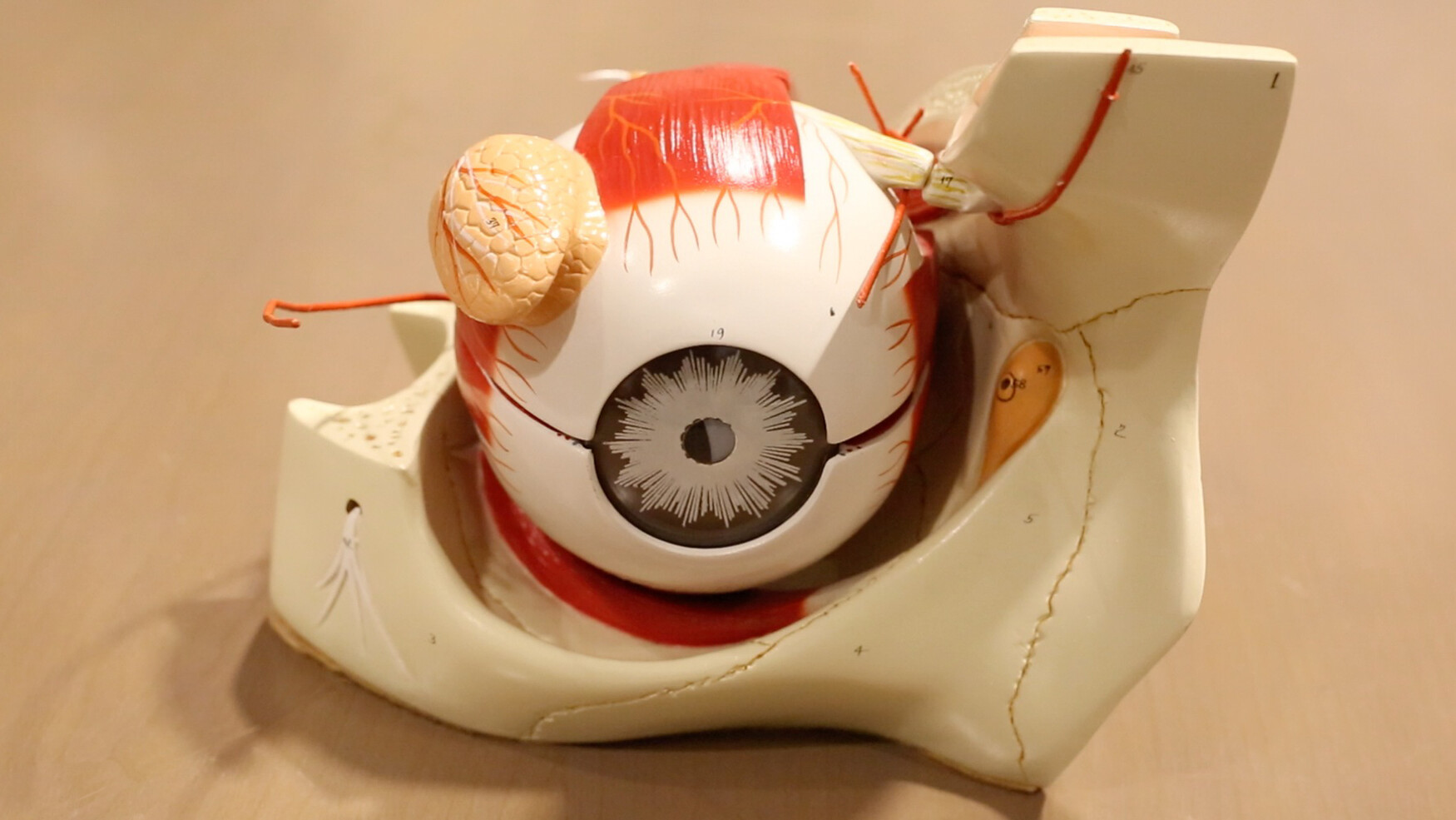

Losing the ability to read is one of the biggest complaints among people suffering from age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The disease causes a distorted or blind spot in the centre of a person’s field of vision. Researchers are finding new ways to help people use healthy parts of their eyes to let them keep reading.

“We’re taking patients who have AMD and helping them use their remaining vision,” said Dr. Martin Steinbach, a professor in the University of Toronto’s Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences and a senior scientist in the Division of Visual Science at Toronto Western Research Institute.

AMD is one of the most common causes of vision loss after age 60. People with a family history, high blood pressure, heart disease, blue eyes and who smoke are at greatest risk of developing the disease.

Steinbach’s lab is helping people with central vision loss to look just above or below what they’re reading so the images can be picked up by a working part of the retina. The process begins with an exam to identify the part of a person’s remaining retina with the greatest potential for retraining.

“We want to make sure that the part of the retina that a person will be using is as close as possible to the part that had been destroyed by the disease, and to make sure that they use an area that is as large as possible,” said research associate Dr. Esther González. “If it is too short, you have to read letter by letter, and that slows you down. If it’s too far away, you can’t read because sharpness decreases as distance from the fovea increases.”

To train the eye, a computer program gives users a variety of single words at print sizes tailored to each individual’s vision. The team asks participants to read the words as quickly and accurately as they could, shifting their gaze where necessary to see the entire word. This allows a new “pseudo-fovea” to be established.

These techniques initially used sophisticated and expensive equipment, which few ophthalmologists would have in their offices. The methods were effective, but the team hopes to help more people by making the training more affordable and convenient.

“We have been developing other techniques that make use of enhanced practice, such as using computer generated words for reading, and this would allow a patient to do their own retraining at home using an internet based instrument or something like an iPad,” said Steinbach. “That would bring it to a wider audience. Hopefully, we can do this so that there is no cost to the patient.”

“It’s a progressive disease and it’s going to affect many baby boomers. And we have a simple way to fix it,” said research associate Dr. Luminita Tarita-Nistor, who was presented with the Envision-Atwell Award for Low Vision Research by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. The team presented their findings at the organization’s annual meeting last month.

Tarita-Nistor also pointed out that central vision loss can have implications extending beyond one’s ability to read. “The fact that these people lose this skill affects their quality of life in many other ways. These patients have a high incidence of anxiety and depression.”