Mobile Menu

- Education

- Research

-

Students

- High School Outreach

- Undergraduate & Beyond: Community of Support

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni

- News & Events

- Giving

- About

Nadia Radovini

A major Canadian study shows the benefit of prolonged heart monitoring to diagnose silent, but dangerous, irregular heart rhythms in people who have unexplained strokes.

Findings of the three-year EMBRACE trial are “an important advance” in determining the cause of up to a third of ischemic strokes, which occur when a clot blocks blood flow the brain, writes Dr. Hooman Kamel in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The journal published study on June 26.

“The results . . . indicate that prolonged monitoring of heart rhythm should now become part of the standard care of patients with cryptogenic (unexplained) stroke,” writes Kamel, who is a neurologist at Cornell University.

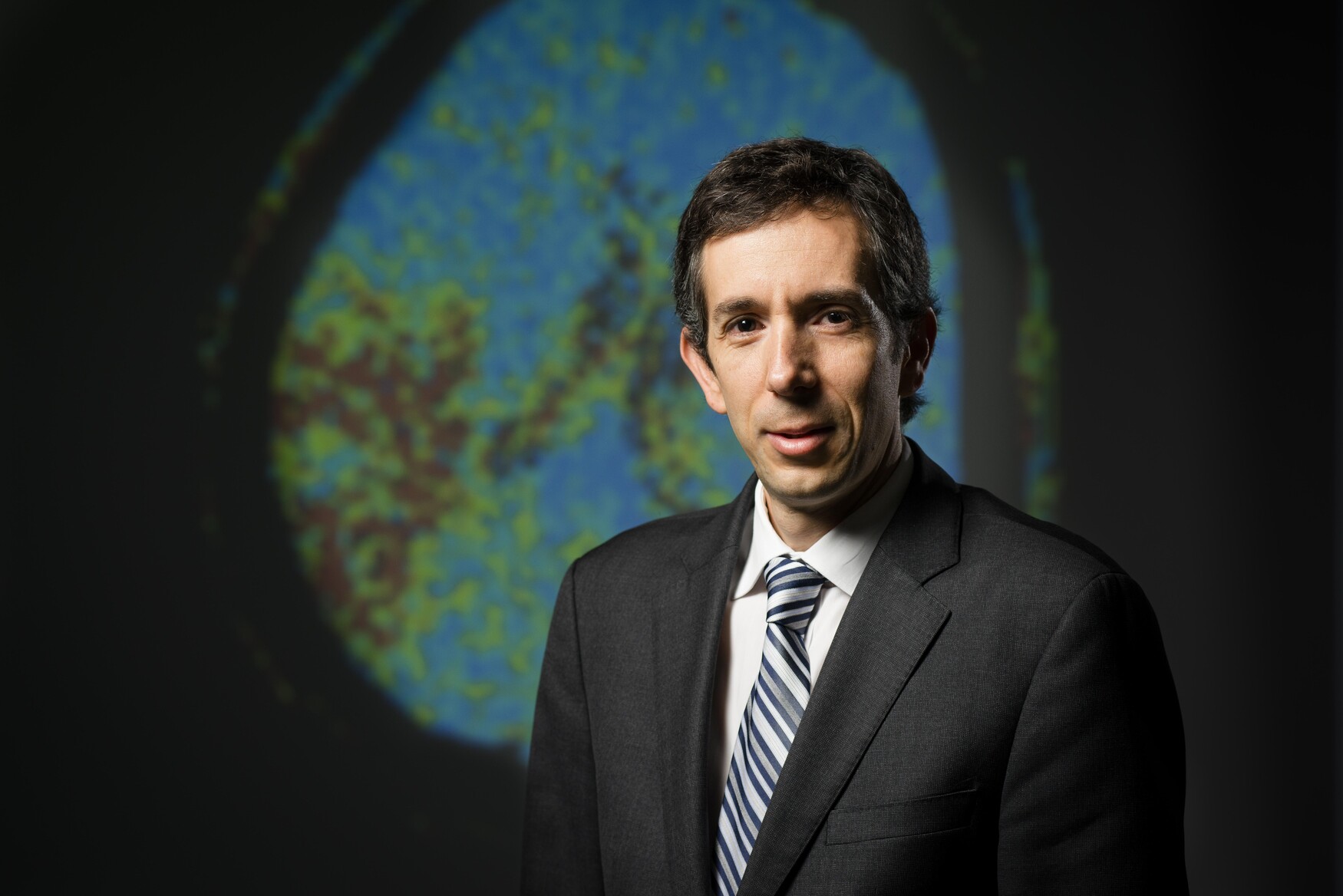

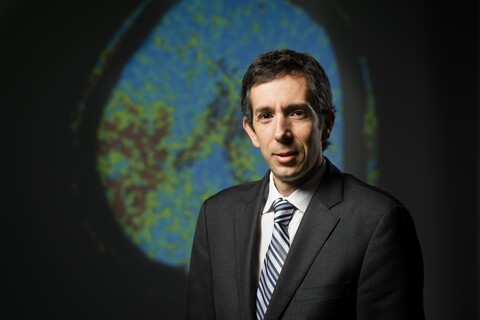

Dr. David Gladstone, an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto and clinician-scientist at Sunnybrook Research Institute, led the 16-centre study. The researchers followed 572 patients ages 55 and older with a recent stroke or TIA (transient ischemic attack, often called a “mini-stroke”), in whom standard diagnostic tests — including conventional heart monitoring for at least 24 hours — failed to detect the cause.

The researchers detected atrial fibrillation (irregular heart rhythm) in 16 per cent of patients, compared with standard 24-hour monitoring, which found the arrhythmia in three per cent of patients. Study participants wore a new chest-electrode monitoring belt for 30 consecutive days.

Prevention of stroke due to atrial fibrillation is “a global public health issue,” according to the study authors, who were funded by the Canadian Stroke Network. Atrial fibrillation causes some of the most disabling, deadliest and costly strokes.

However, it is often hard to diagnose because the irregular heartbeat may last for just a few minutes, after which the heart reverts to its normal rhythm. Unless an individual is wearing a heart monitor at the time it occurs, there is usually no diagnosis.

In practice, stroke patients have traditionally received only short-duration heart monitoring (e.g., for 24 hours) to screen for atrial fibrillation — a strategy that now appears inadequate. “The harder we look with more intensive heart monitoring, the greater the chance of finding this hidden risk factor — it’s like medical detective work,” said Gladstone, whose research was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation (HSF) and the HSF Canadian Partnership for Stroke Recovery.

In the study, enhanced detection of atrial fibrillation led to significantly more patients getting stronger anti-clotting medications to prevent recurrent strokes.

Atrial fibrillation is a risk factor for stroke because it can promote the formation of blood clots in the heart that can travel to the brain. It is important to detect because it can be effectively treated with certain anti-clotting medications, which cut the risk of clots and strokes by two-thirds or more.

Gladstone has already begun implementing the study’s findings in practice by offering prolonged heart monitoring to patients at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, where he directs the Regional Stroke Prevention Clinic. “With improved detection and treatment of atrial fibrillation, the hope is that many more strokes and deaths will be prevented,” Gladstone said.

The New England Journal of Medicine published a second U.S-based study on prolonged monitoring this month, called CRYSTAL AF, which further supported the practice change.

Investigators of the Canadian Stroke Consortium conducted the EMBRACE trial, with coordination by the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital.

Photo by Doug Nicholson.